Parks and Recreation in East St. Louis

Andrew J. Theising

This itinerary will explore Parks and Recreation in East St. Louis, specifically by directing you to four locations in the greater East St. Louis area and sharing parts of their geographical and social histories. The State of Illinois authorized the creation of special taxing districts statewide for the purpose of supporting parks, forest preservation, and scenic byway protection as early as 1893.1 The legislation evolved over time, and by 1911 a state level park commission was created that spawned considerable park development across Illinois.

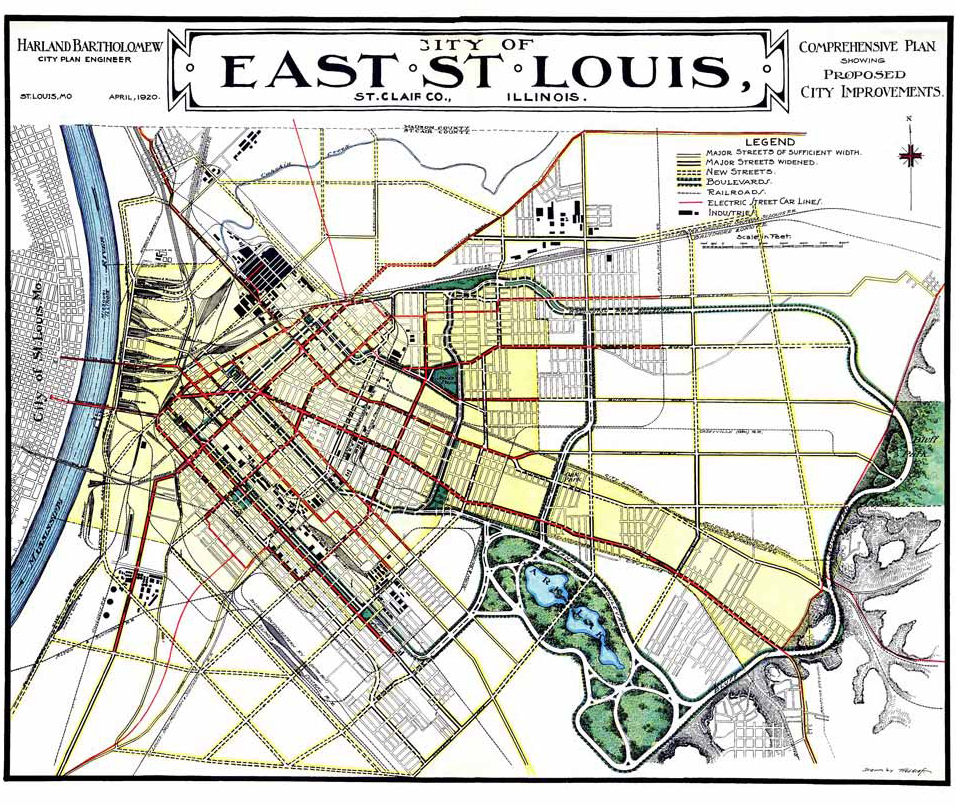

1920 East St. Louis Comprehensive Plan. Showing proposed park system. From Harland Bartholomew, City Plan for East St. Louis; 1920.

While this action seems like one noble cause among many during the Progressive Era, it had political overtones. Illinois has an individualistic political culture, according to Daniel Elazar, and this culture adds a corrupting “marketplace” dimension to all of its politics.2 This culture is abundantly evident in the American Bottom generally, and East St. Louis particularly, where land use was driven by economic uses first and social uses second. Across the American Bottom can be read the economic imperatives of industry, rail, and political patronage, with scant attention paid to the diverse publics living in the region. It was the goal of many Progressive Era reformers to address this dominant orientation by breaking up big-city power through the creation of boards and commissions. However, in individualistic places like Illinois, it pushed the public’s business out of public view, and these various boards and commissions became political pawns for patronage and corruption. The Park District, the Levee and Sanitation District, the School District, and the Health District all became sources of political influence and proving grounds for city hall aspirants. This is not to say, however, that these districts did not do their jobs, and sometimes do them well.

Parks played an important societal role at the turn of the last century by providing one of the few public counterpoints to the harsh individualist and economic orientation of prevailing land use practices. The development of parks reflected a general value of providing open space in the city and the respite a natural setting could give to residents. Once the choice sites were taken for industrial purposes, and the secondary sites were taken for housing and commercial uses, the remaining sites were available for social or recreational use. Fortunately, many of the features that make a site less desirable for industrial or large-scale residential purposes (hills, woods, water), render it ideal as a site of recreation. With recreation seen as a necessary break from factory life, and parks understood as playing a pedagogical role for both individuals and society, the National Recreation Association wrote in 1936: “Fun is the birthright of every child and the prerogative of every adult.”3 Progressives demonstrated that parks and playgrounds were essential elements of urban life, noting how “The playground, almost unknown at the beginning of the century, has become widely recognized as an essential community feature.”4 An effective park system meant that schools would have better children, factories would have better workers, and the community would have better citizens. St. Louis’s Charlotte Rumbold, a leading figure in the playground movement locally, said it best: “if we play together, we will work together.”5

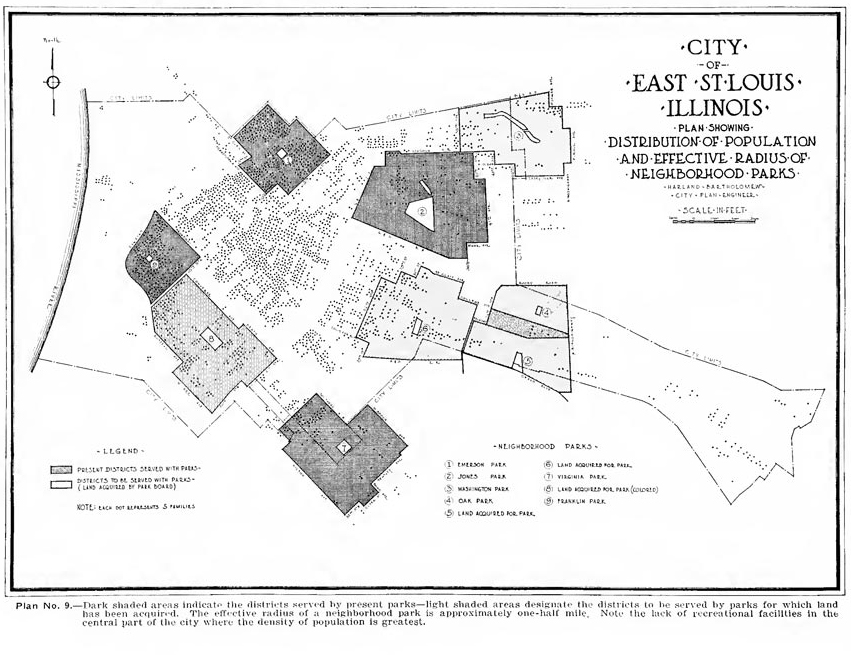

East. St. Louis Plan showing neighborhood Park distribution and population. Note existing vs. proposed parks. From Harland Bartholomew, City Plan for East St. Louis; 1920.

Parks were a great equalizer, as they were open to all incomes and backgrounds (though, as we will learn later, parks were segregated, too). Houses at the time were small and often crowded with many children, so the home was not seen as a place for entertainment as it is now. This meant that children sought diversions outside of the home. The open fields and playgrounds of neighborhood parks were a boon to all. This need, coupled with the tradition of the Sunday family outing that was so popular during the Progressive Era, made recreation more than just a social need—it became a public good that government took on as a tax-supported public service.

The East St. Louis Park District was created in 1908 and consisted of some or all of three townships (townships are the political subdivisions of counties): East St. Louis Township (which was the city proper of East St. Louis), Canteen Township (the area north of East St. Louis, which includes the communities of National City and Washington Park), and Centreville Township (which includes the cities of Centreville, Monsanto/Sauget, and Cahokia).6 In this itinerary, you will be taken to four parks across the district—where each park will be described by the geographic story of that particular site, the personal story of someone associated with the park, and the neighborhood story of the surrounding places.

Frank Holten State Park

5753 Lake Drive

East St. Louis, IL 62203

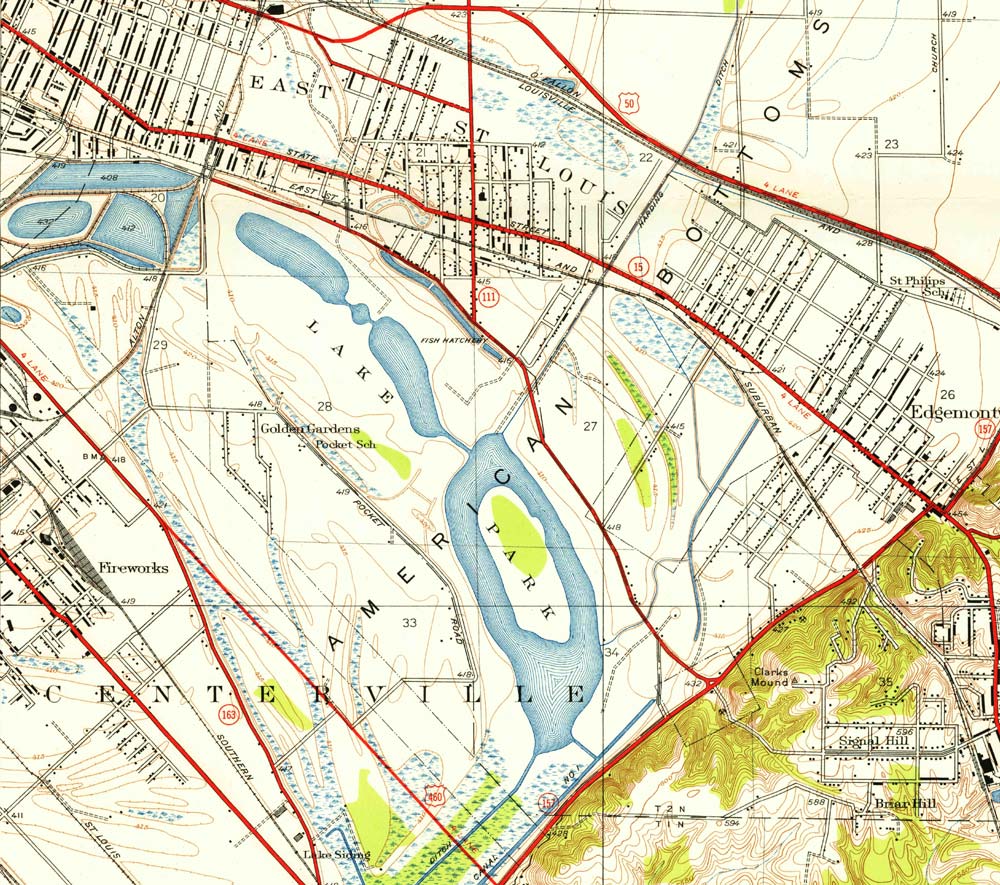

1931 map showing topography of marshes and lakes in Frank Holten Park—designated here as “Lake Park”. From “French Village, ILL” USGS 7.5 minute map.

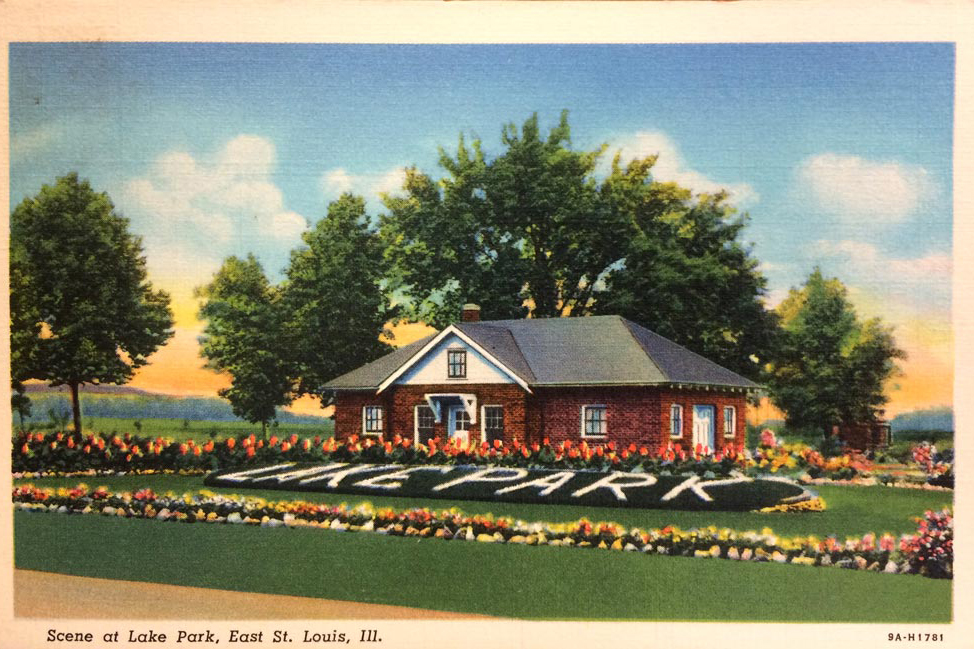

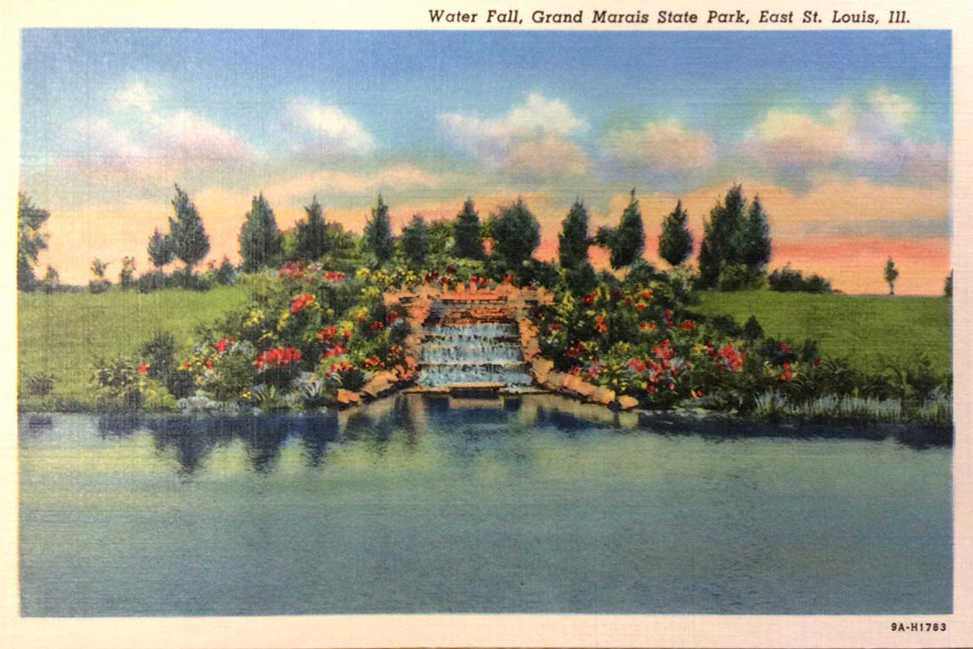

This gigantic expanse, covering over 1,000 acres, has gone by three different names. It was first acquired by the East St. Louis Park District in 1932 and called “Lake Park.” At the time, it was the third largest municipal park in the United States.7 The park district could not sustain the large park, and park improvements proved difficult. In 1941, after a front-page story of the park appeared in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, a complaint was made to President Roosevelt that the park was nothing more than a sign of East St. Louis corruption. By 1964 Lake Park was turned over to the State of Illinois. The State renamed the park using the geographic area’s historic name Grand Marais (French for “large swamp” or “great marsh,” and often mispronounced “muh-RYE-ess,” leading to the frequent misspelling “Marias”). The park was renamed Frank Holten State Park on May 1, 1967, after Representative Holten passed away.8

Entrance to what was then “Lake Park,” probably about 1940. ESL Parks often used live flower plantings to spell out names of parks, as shown here. The site bore the name Lake Park from 1932 to 1964. from the Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE

One of the grandest events held here was the annual Lady of the Lakes Pageant. Each October, a local beauty was chosen to lead this autumn festival, which included a ball at the Ainad Masonic Temple and performances on a lakeside stage. An orchestra and choral groups performed, as did dancers. Actors performed skits representing the history of Illinois. Upwards of 10,000 people attended.9

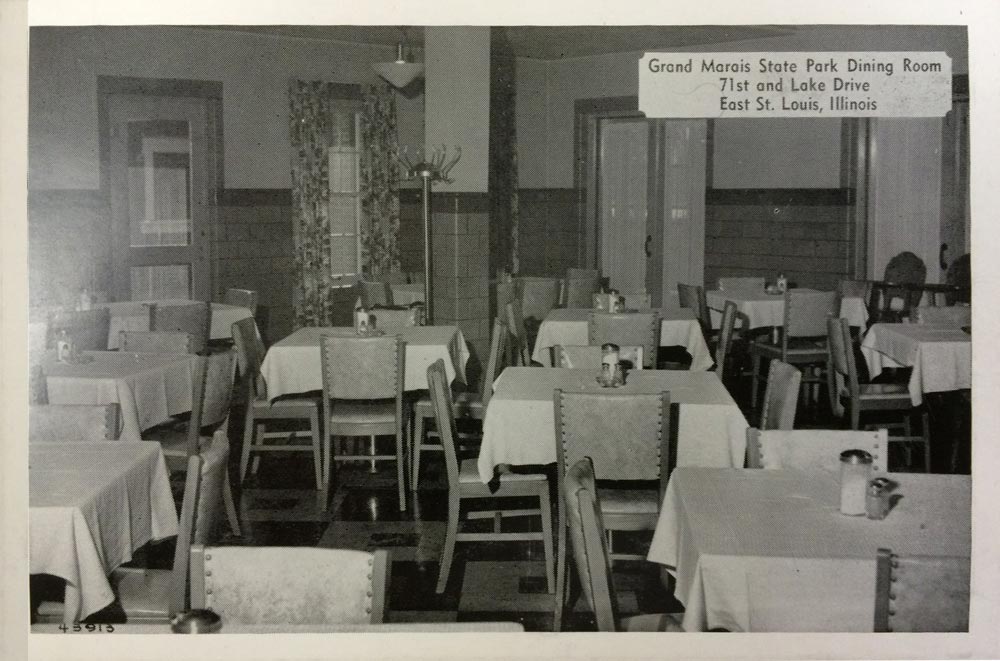

Dining Room during the “Grand Marais” years (1964-1967), from the Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE

There are over 200 acres of water and five miles of shoreline. There was an attempt to build a swimming pool in 1938—but the concrete cracked, and the pool was deemed infeasible and never opened. Some say that pool failed to open since African Americans were demanding access to the new facility.10

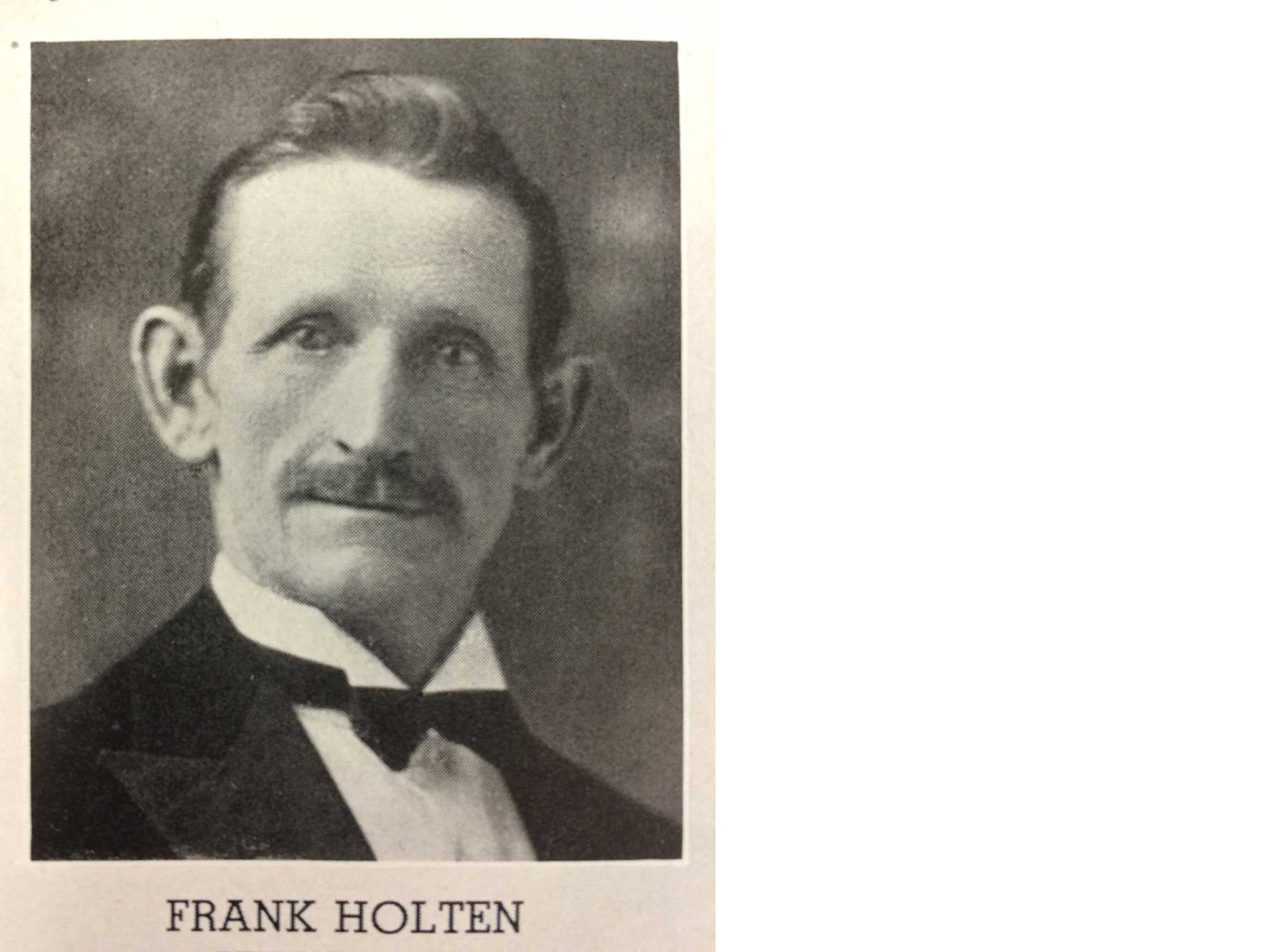

State Representative Frank Holten, 1927. from the 1927 Illinois Blue Book, Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE

Frank Holten was the longest serving elected official in the history of the Illinois legislature. He was first elected in 1916 and served until his death at age 98 in 1966. He was defeated in 1942 for only one term (by his Republican brother-in-law) and returned to office in 1944.11 He was in the coffee and tea business professionally, and belonged as a violinist to the Musicians Union, which he helped create. He was an early advocate for labor unions when there were few such voices in state government. He supported the eight-hour workday and pushed for women’s right to serve on juries in Illinois. He had only a sixth-grade education but possessed a “winning personality” and a “knack for showmanship.”12

He owned the Old Home Tea and Coffee Company and was quick to offer complimentary refreshments for church events. His eight-piece band, formed in 1898, participated in public parades, performed at the Fairmont Race Track, and played at private parties. He was remembered as never making rash promises but for saying “tell me what you want” and “I’ll try to get it for you.” 13

On his 95th birthday, President John F. Kennedy sent him a telegram that said, “your nearly fifty years as a member of the Illinois House of Representatives is testimony to the high esteem in which you are held by the people of Illinois.”14

Google Earth screenshot showing the northern lakes of Holten Park (right) and the cleared dirt of the old Alcoa site (left). Pollutants from the factory site were dumped into the nearest lake.

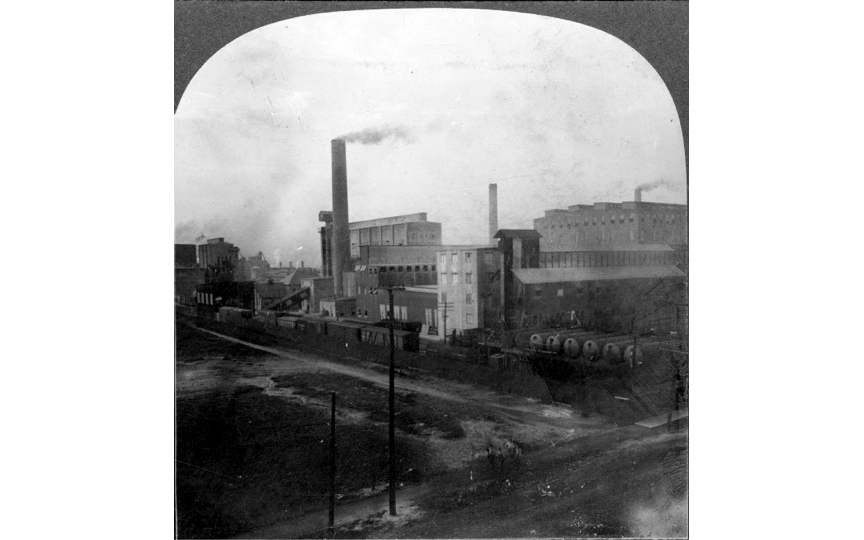

Frank Holten Park is adjacent to the old Alcoa site, where Alcoa’s Aluminum Ore Company division operated off Missouri Avenue. The buildings are long gone. Directly across the street from the Alcoa site was the Alton and Southern Railroad, which was Alcoa’s railroad for hauling its products and fuel. Aluminum Ore was the largest employer in the area. There was a large refinery here for bauxite ore and a factory that made aluminum kitchenware.

The Aluminum Ore Company, a division of Alcoa, about 1910. from the Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE

This area is outside of the East St. Louis city limits in the city of Alorton, a name derived from the words ALuminum ORe TOwN. This was a strategy of many industries—locate around East St. Louis but not in it. East St. Louis had a large population and needed to tax for the services required by that population—schools, parks, and public health. By locating outside the city limits, large factories could tap the labor pool without having to finance city operations. The profit margins at these factories were very low, and the wages were poor. Corruption was common. Sadly, the cities of East St. Louis and Alorton struggle with corruption to this day.

The Aluminum Ore plant was at the root of a tragic historical event: the 1917 Race Riot, probably the bloodiest riot in history of the United States. Labor unions were for whites only, and white workers went on strike over wages. African Americans were recruited from Southern cities to come north and work at the factory. Having lived the sharecropping life, these workers were thrilled to earn a fraction of the wages being pursued by the strikers, and they had no idea of the circumstances under which they were arriving. On July 2, 1917, inflammatory speeches were made at a great meeting in the Labor Temple on Collinsville Avenue. White workers poured out of the building and marched in military formation down Collinsville Avenue to Broadway, where innocent blacks were violently accosted. Whole neighborhoods were burned, and there were many lynchings. The official death toll was 39 blacks and 9 whites, but the real toll was probably over 100.15

The plant began to downsize in the late 1950s and was closed in the early 1960s. Unfortunately, years of bauxite refining at the Aluminum Ore plant took an environmental toll on Holten Park. According to the US EPA, Alcoa dumped refining waste materials into the lakes at various points during the twentieth century, likely beginning before it became a park. Dikes built to hold the waste were breached. In 2014 Alcoa began cleanup of the site under EPA supervision.16

Lincoln Park

606 South 15th Street

East St. Louis, IL 62207

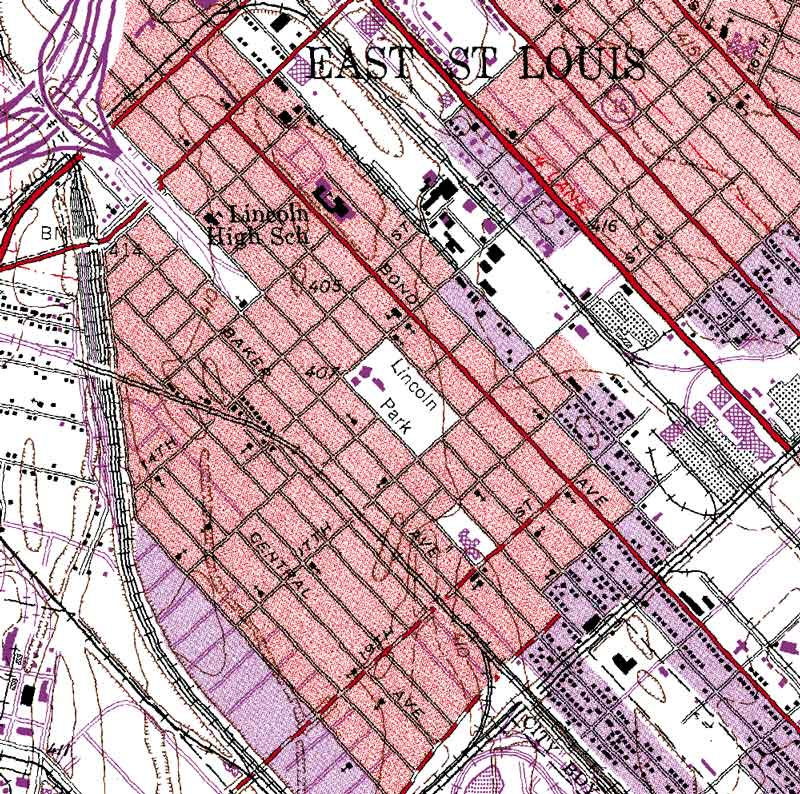

1954 (revised 1993) map showing urban context of Lincoln Park. From “Cahokia, ILL.–MO.” USGS 7.5 minute map.

Lincoln Park is a simple park covering two city blocks in East St. Louis’s South End neighborhood. Designed in 1907, this park was exclusively designated to serve the African American community. The growing population of African Americans migrating from the South placed an increased demand on government services. With the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision establishing separate but equal as the legal standard, segregated services were provided for parks, schools, and even healthcare. (Private sector discrimination in terms of housing and commercial establishments was already segregated and unaffected by Plessy.) Lincoln Park has walkways lined with catalpa trees, which flower beautifully in the spring, and also houses a now-abandoned swimming pool that sits murky and cordoned off by a chain-link fence. It is located between 15th and 17th Streets (now M. R. Lemons Boulevard), and between Piggott and Market Avenues, just one block south of Bond Avenue. The park features a playground, picnic areas, shaded walkways, and a community center. Piggott Avenue is named for James Piggott, a Revolutionary War officer who established the first ferry service between St. Louis (then Spanish Territory) and what is now East St. Louis back in 1792. He served as a territorial judge based out of Cahokia, the ancient Native American city reestablished by the French as a mission in 1699.

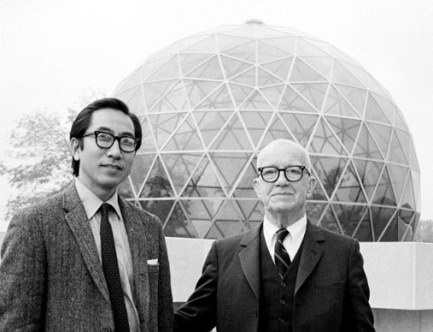

1. Buckminster Fuller pictured here in front of his dome on the Edwardsville campus. From SIUE.edu

2. The dome of Lincoln Park's Multipurpose Building, 2017. Photography by Jennifer Colten.

Richard Buckminster (Bucky) Fuller (1895–1983) was an architect, inventor, and futurist. In 1971, this world-renowned architect came to East St. Louis with a plan. He sought to re-envision city living by incorporating a massive one-mile-diameter geodesic dome over part of Centreville Township at the request of city leaders. Fuller was a faculty member at Southern Illinois University’s Carbondale campus from 1955 to 1970. He described his urban dome as a “quarter-sphere transparent umbrella” mounted high above the city, with room for 125,000 residents below.17 In Lincoln Park, he built a prototype to illustrate his invention, geodesic dome construction. The dome presently serves as The Mary Brown Center, a community center operated by the Lessie Bates Davis Neighborhood House, a local service nonprofit. It has a gymnasium, a computer center, and access to social services and recreation programs.18

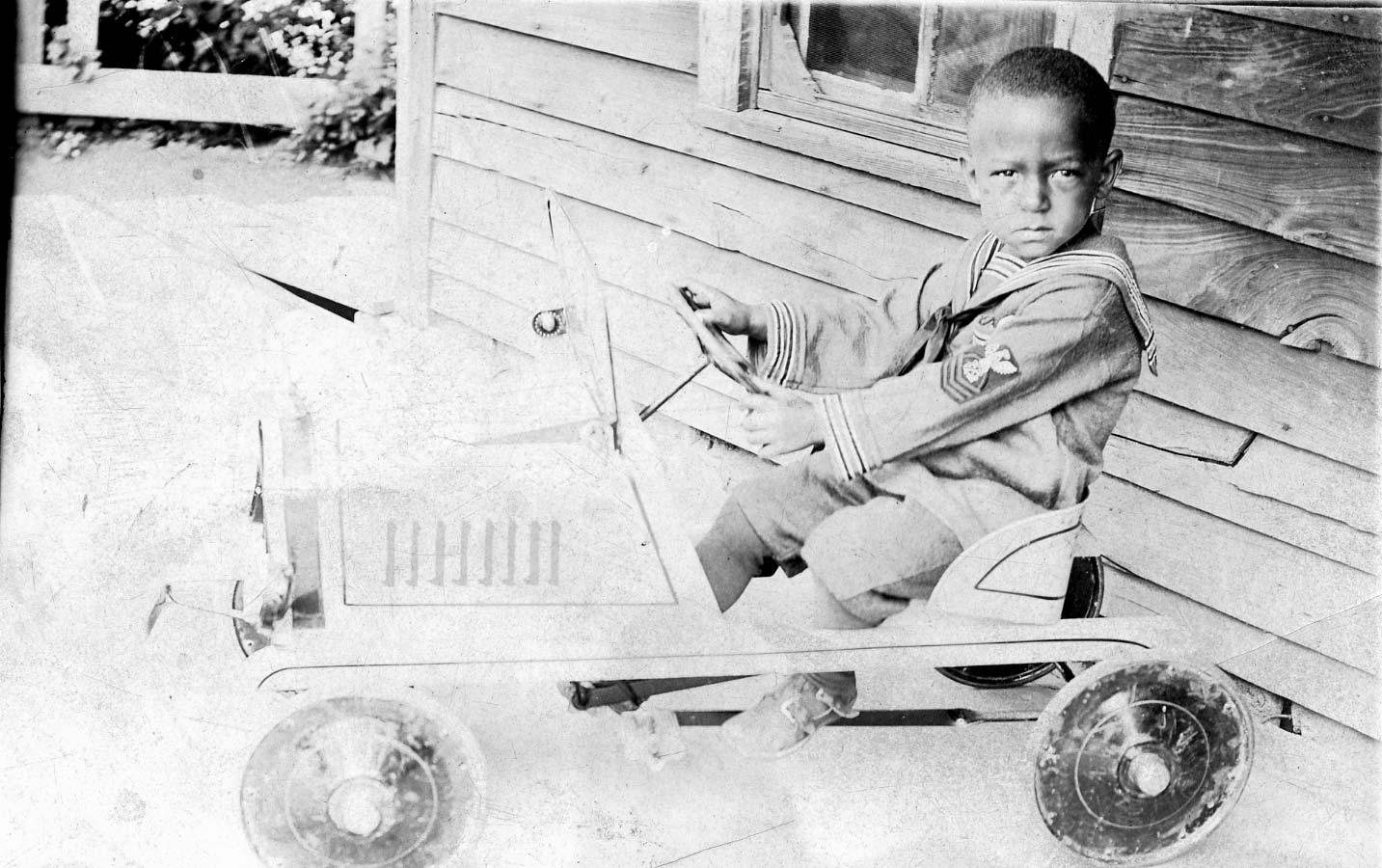

1. A young East St. Louis boy riding a toy car, circa 1920. Digital image from the collection of Reginald Petty. SIUE Institute for Urban Research

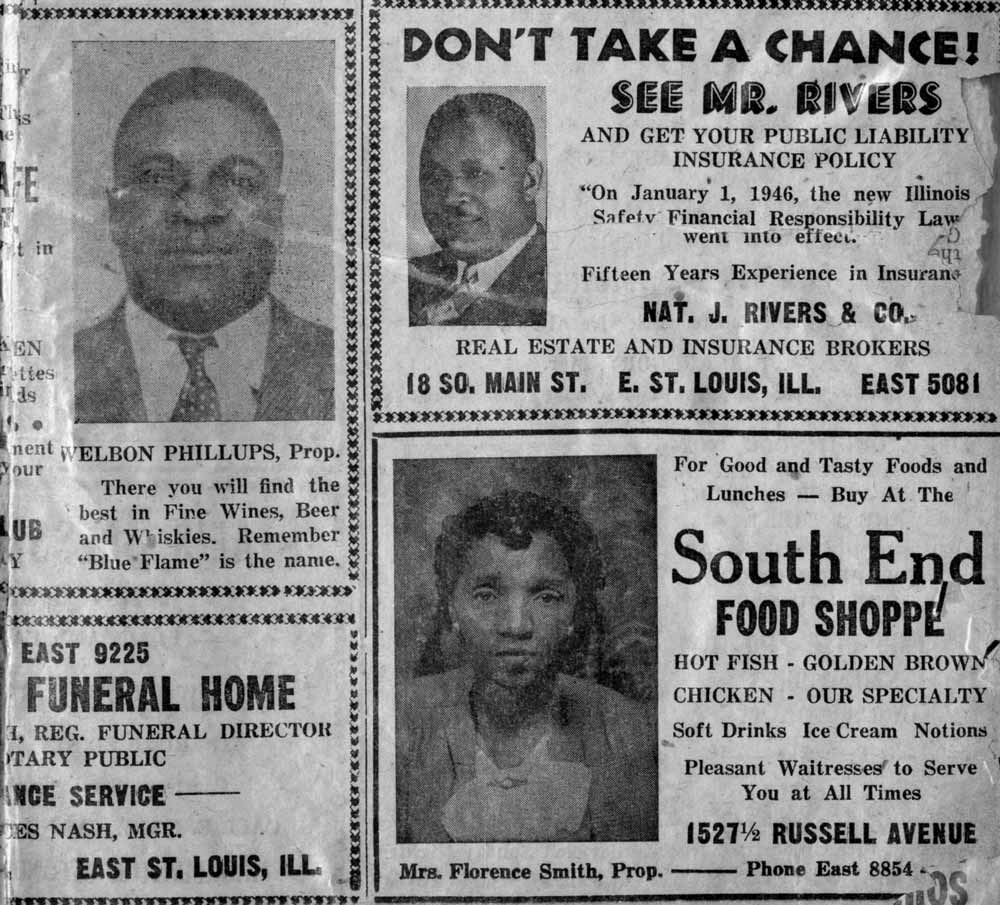

2. Detail from a page of advertisements from the old East St. Louis Citizen, including the South End Food Shoppe. Reginald Petty Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE.

The South End neighborhood was the residential place for African Americans, and Bond Avenue was its main street. Segregation was illegal in Illinois but certainly existed throughout southern Illinois—which behaved more like neighboring Missouri than upstate Chicago-land. This de facto segregation kept the African American population in the South End, as well as within some other small clusters such as Franklin Bottom near the present-day Casino Queen. There was little interest in the broader society to challenge these divisions, especially since previous efforts met with failure in the courts. Though unjust in a significant way, the arrangement was made to work by people on both sides. Black institutions emerged, black newspapers arose, black businesses flourished, and black schools were centers of quality and creativity.

Bond Avenue to this day shows an array of housing styles that reflected the diversity of backgrounds represented in the African American community. Doctors and lawyers resided among floor sweepers and laborers. Though segregated by race, the community was diverse economically. Churches, schools, and neighborhood businesses were abundant on Bond Avenue and the streets radiating from it.

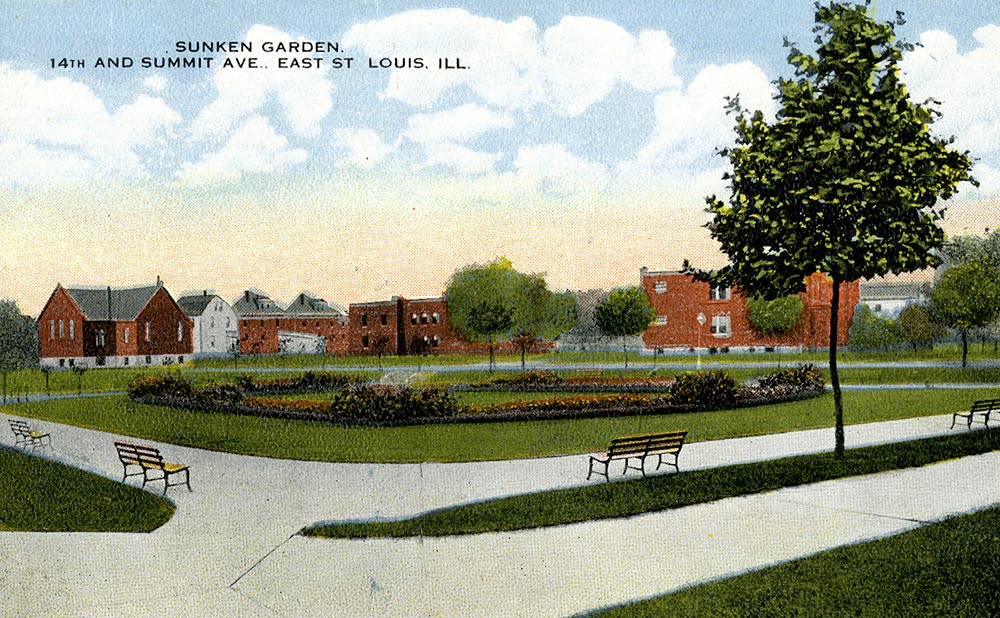

The Sunken Garden

Summit Ave and Pennsylvania Ave

East St. Louis, IL 62205

Sunken Garden occupies Block 9 of Wolf’s Subdivision and the small yellow triangular remainder of the Resubdivided Block 5.

This small park is in a sunken area that is about five feet below grade in the pocket formed by the intersecting streets of Summit and Pennsylvania Avenues. Another prominent street beginning at this intersecting point is Washington Place to the southwest. The entire neighborhood was once part of Wolf Farm. Beginning in 1901, Phillip Wolf decided to sell off his farm and develop it into high-end homes.

Postcard of the Sunken Garden, with flower beds in the center, circa 1930. Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE

The Sunken Garden is sometimes referred to as Olivette Park (named for Olivette Wolf), which is also the name given to the neighborhood. It was a vacant lot that had been used for summer events through 1912, when the city decided to improve the space and add a drinking fountain. Over the years, the small park became known for its lavish landscaping; the sloping sides of the park were planted with beautiful flowers and park benches allowed people to rest and enjoy the introspective space. Play equipment was added in later years. Today most of stately trees that ringed the park are long gone.

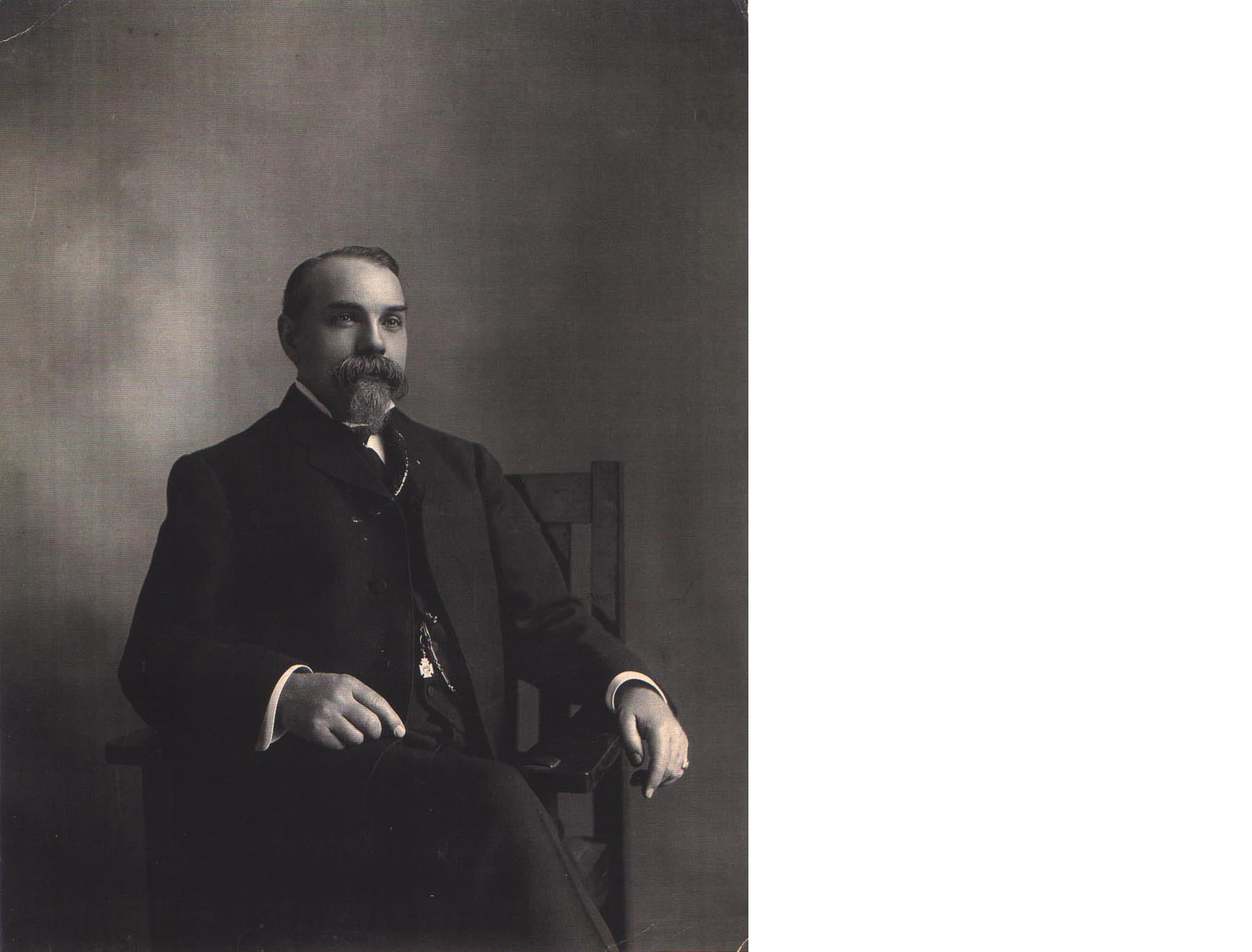

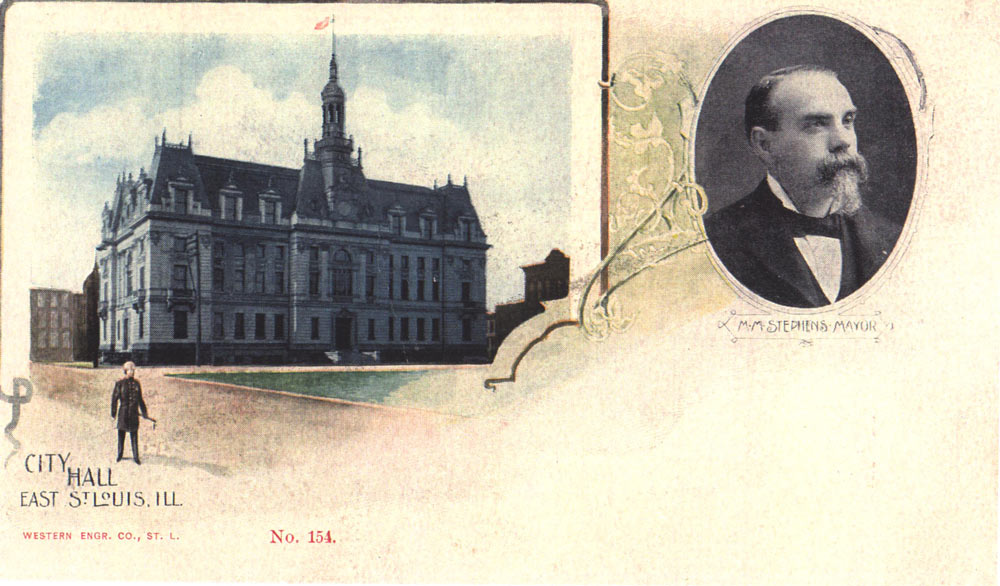

1. M. M. Stephens, whose mansion stood at 1010 Pennsylvania Avenue in Olivette Park. Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE.

2. Postcard showing M. M. Stephens as mayor, along with the new city hall building. It opened in 1900 after the old one was destroyed in the 1896 tornado. Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE.

Malbern Monroe Stephens was an innkeeper, a politician, a capitalist, and (at one time) the wealthiest man in East St. Louis. He had two presences in this neighborhood. The Stephens House Hotel was constructed at what would be the intersection of 5th Street and Summit Avenue. (The building stood until 2014.) Stephens then built his grand mansion in 1903 at 1010 Pennsylvania Avenue (no longer standing). He was a member of the First Methodist Church, which used to stand on 11th Street between Pennsylvania and Summit. (The church tower of this old building has been rebuilt as the castle on the back lot of the City Museum.)

Stephens was the greatest mayor East St. Louis has ever known. He served 22 non-consecutive years as mayor between 1887 and 1927.19 He was a reformer who pushed through major public improvements, including raising the streets of downtown out of the floodplain. (You still can see today how the streets of downtown are 12–15 feet higher than the lots.) The corruption that defined East St. Louis politics in the 1860s and 1870s disappeared under his first stint as mayor. Population grew and industry (like Alcoa) flocked to the city on his watch. He was defeated by political machine interests in 1903, and the corruption returned.

After the 1917 Race Riot, the broken city begged Stephens to return to office and bring peace and prosperity back. At age 72, he reluctantly came out of retirement to support and lead his city. He served from 1919 until 1927 and presided over a period of calm and healing. 20 He was defeated in 1927, again by political machine interests that then returned the city to its illicit path. A bad investment in St. Louis’ Victoria Building bankrupted him in 1916.

Jane Stephens, daughter of M. M. Stephens, in the front yard of 1010 Pennsylvania Avenue. Her “nurse” watches over her. Stately homes are in the background. Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE.

Each Sunday, according to his daughter Jane, he would walk from 1010 Pennsylvania Avenue to the center point of the Eads Bridge and then back again. She remembered that he refused to eat chicken because he did not think much of the scavenging bird as a food source. A rule in his house was that you could not come down from the second floor until you were dressed for the day.

1. A 1914 image of a newly-renovated Sunken Garden. The tips of the First Methodist church tower are visible above the roof of the house at left. From the Emmett Griffin Papers, donated by Patricia Bechtoldt, and part of the Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE.

2. The park in 2017: Photograph by Jennifer Colten.

The Sunken Garden is located in Olivette Park, the city’s mansion district once called by some “quality hill.” Important politicians lived here, including M. M. Stephens at 1010 Pennsylvania and his arch-rival city attorney and later municipal judge Maurice V. Joyce across the street at 1005 Pennsylvania (present home of the Katherine Dunham Museum). The two faced off in the 1909 mayoral election—and both lost. Real estate baron Thomas Fekete lived next door to Stephens. On Washington Place lived Fred Gerold (the only East St. Louis politician found guilty of corruption at trial back in the day), corrupt political boss Locke Tarlton (the man behind the machine who orchestrated Stephens’ defeats in 1903 and 1927), and city judge and mayor Silas Cook. All of these home sites are vacant lots now. The Katherine Dunham Museum houses the collections of the late great dancer, actress, and anthropologist. Dunham was an artist-in-residence at Southern Illinois University’s Carbondale Campus in 1964 and came to East St. Louis when SIU established facilities here and in Edwardsville. She fell in love with the community, maintained a residence here, and took over the old YWCA building (originally the Joyce mansion) for her museum.

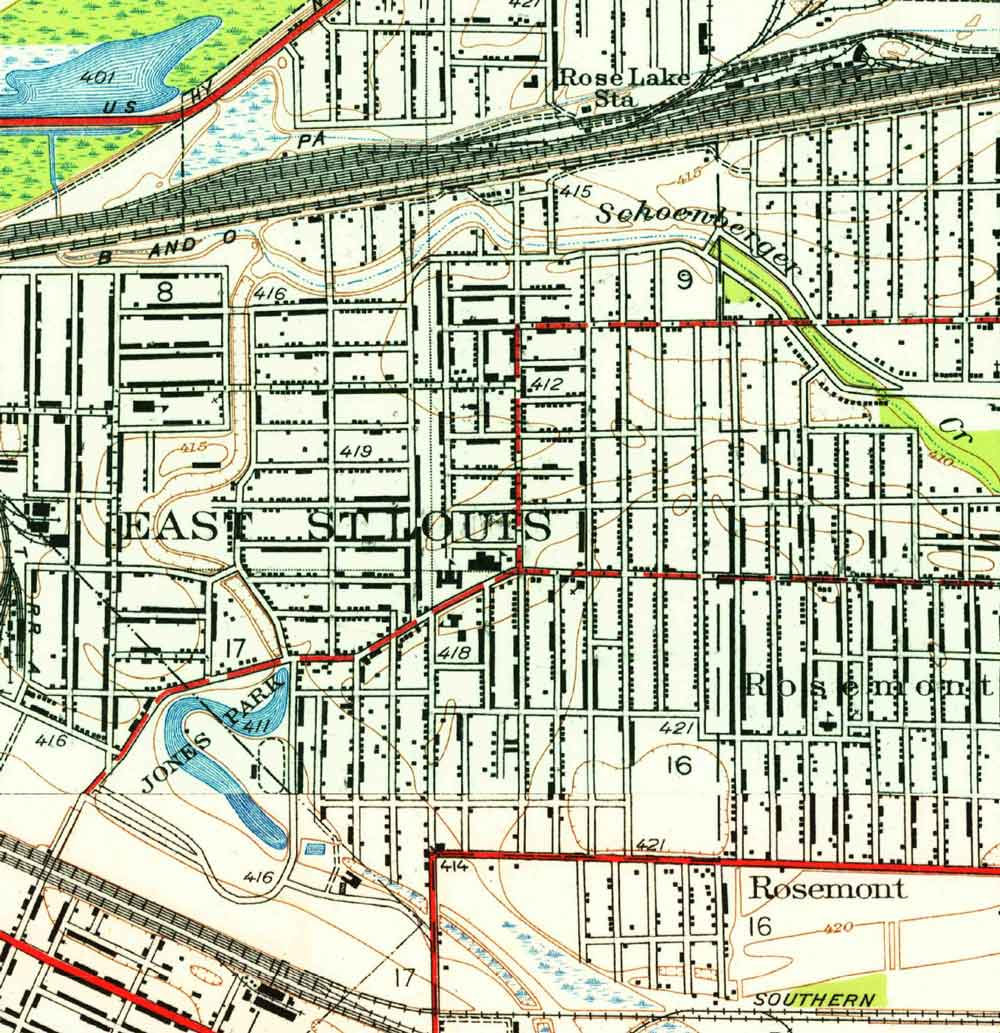

Jones/Lansdowne Park

2500 Argonne Drive

East St. Louis, IL 62201

1931 map showing Jones Park and its topographic connection to the former Lansdowne Park and Schoenberger Creek to the North. Compiled from “Monks Mound, ILL.” and “French Village, ILL.” USGS 7.5 minute maps.

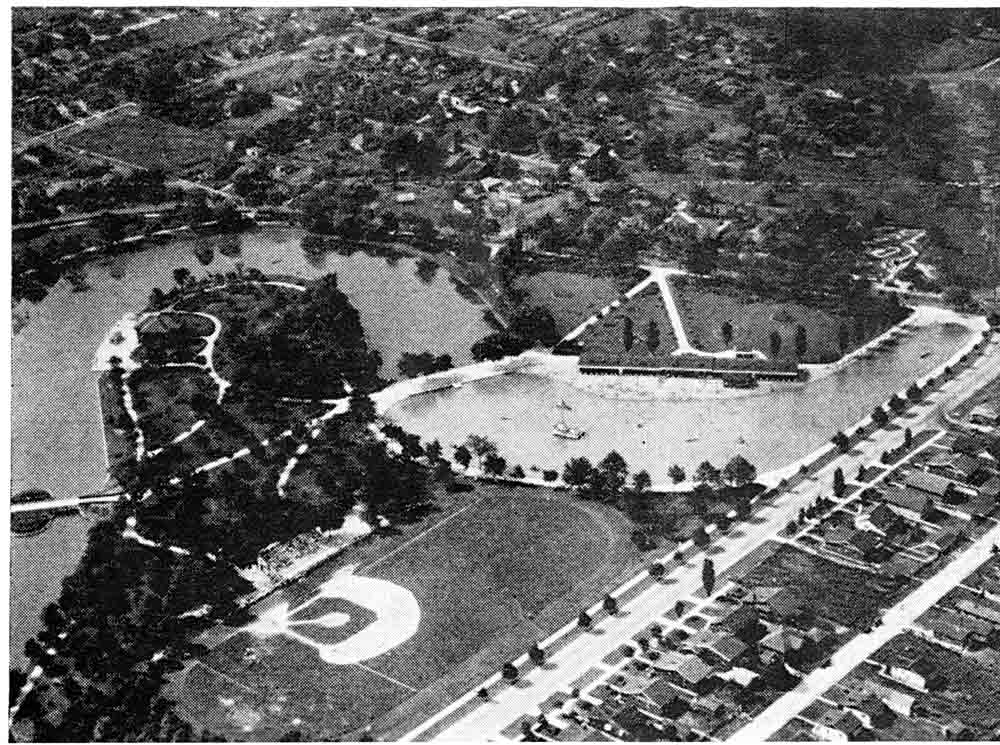

This area was once in fact a double park in the city’s Lansdowne neighborhood—though at present only Jones Park still remains. While the history of the two parks is not documented well, Lansdowne Park probably was stablished as the first of the two, possibly as early as 1901—pre-dating the park district itself. The Jones family donated adjacent farmland to the park district by 1912, thereby creating Jones Park. At some point after 1926, Lansdowne Park was closed, and the property was either attached to Jones Park or sold to developers, or both. There is a large lake still there today, which is all that remains of a massive three-and-one-half acre water feature that was shared between the two parks.

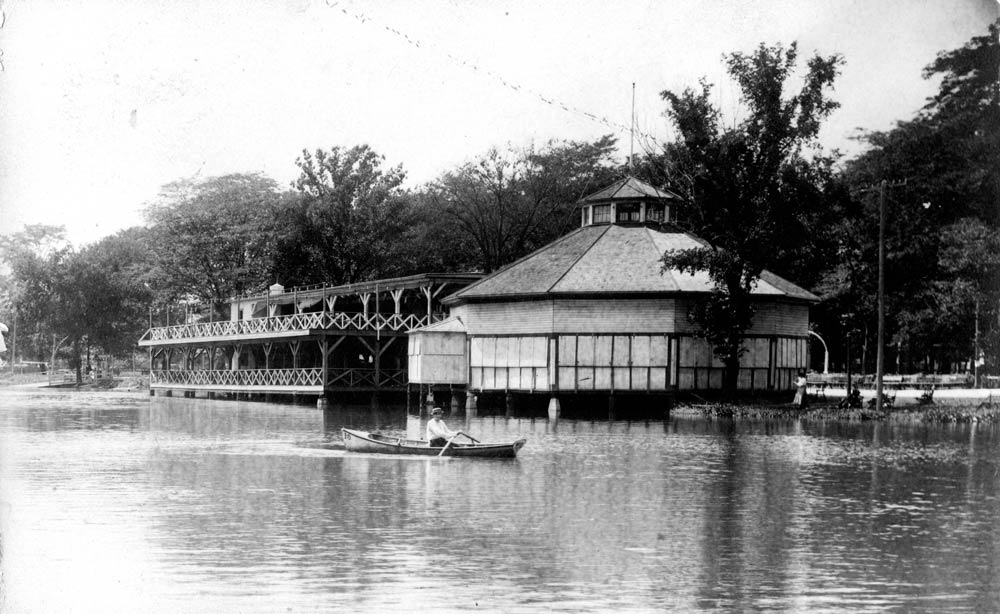

Boating at Jones Park and Lansdowne Park, circa 1920. Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE.

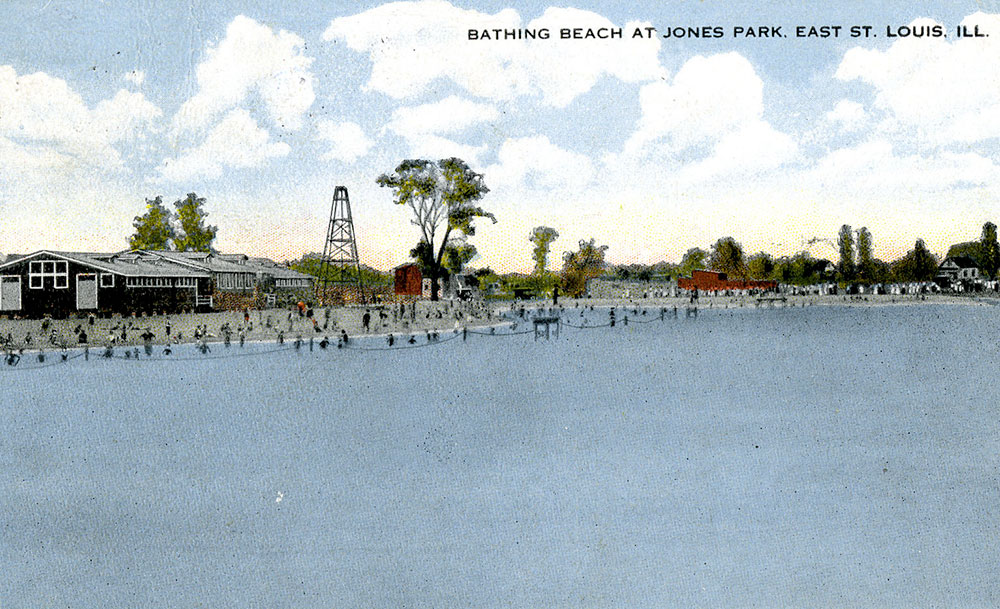

Swimmers enjoying the “bathing beach” at Jones Park, about 1930. Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE.

In fact, Lansdowne Park seems to have been designed around the boating pond, as is still legible in the curving street pattern and swale north of Jones Park. In 1913 Jones Park was expanded with facilities, when $25,000 was invested to create a bathing beach for swimmers. Some called the newly constructed water feature the largest inland beach of its kind in the United States.21 One million gallons of fresh water were pumped into the pool daily through an elaborate fountain system.22

Labor Day parades were big events in this union town, and massive parades wound their ways through the streets of East St. Louis. Twenty thousand workers representing seventy labor unions marched in the parades, with another fifty thousand watching along the way.23 The Congress of Industrial Organizations (the union association for unskilled workers) marched first along a route that ended at Lansdowne Park. The American Federation of Labor (the union association for skilled workers) marched second, taking an even longer route that ended at Jones Park. Both parades ended, incredibly, with a picnic for thousands in the two parks.

Jones Park Bandstand, early 19th century:Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE.

The Bandstand in 2017: Photograph by Jennifer Colten.

A 1931 street guide described Jones Park as being one of the finest parks around. The park contained 130 acres and featured facilities for tennis, football, horseshoes, quoits, and baseball. A quarter-mile track surrounded an athletic field. The lake’s lagoon was used for canoeing in the summer and for ice skating in the winter. There was even a small zoo on the property where peacocks would wander.24

Two memorials to veterans stand at the park. A war memorial was built in 1924 near the entrance to the park at North 25th Street and Caseyville Avenue to honor the citizens who died in World War I, with each face representing major wars: the Revolutionary War on one side, the Civil War on the second, the Spanish-American War on the third, and the Great War on the fourth side. A second memorial was built showing a Civil War solider to honor all veterans just inside the park. The soldier standing guard was nicknamed “Julius” after an elected official declared the statue looked like his uncle.

Emmett Patrick Griffin. SIUE Institute for Urban Research.

Emmett Patrick (Pat) Griffin was the long-time superintendent of the park district. He graduated with a degree in civil engineering from University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 1907. His first job was with the new East St. Louis Park District in 1908. After the untimely death of the first superintendent, Griffin was given the promotion—a job he would hold for the rest of his life.

He took deep interest in the parks and recreation movement of the Progressive Era. There was a belief that parks represented a public good, providing respite and interaction with nature for those who toiled long hours at labor. East St. Louis was filled with factory workers and Griffin saw to it that respite was available. In addition to running the park system, he belonged to many professional organizations and was proud to show off his park system to visiting professionals and conference attendees.25

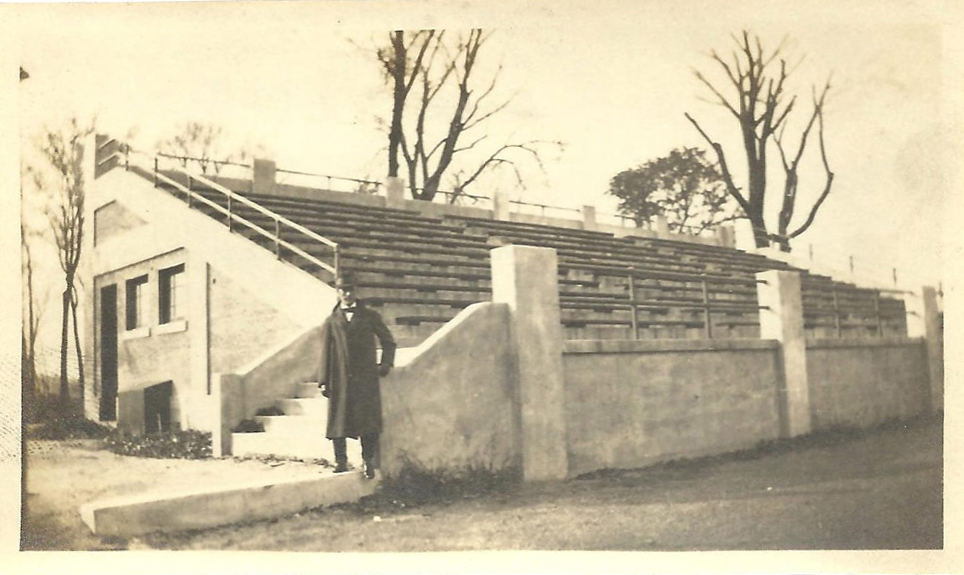

Emmett Griffin poses by the bleachers and comfort station at Jones Park, 1914. From the Emmett Griffin Papers, donated by Patricia Bechtoldt, and part of the Andrew Theising Research Collection, Bowen Archives, SIUE

Contemporary photograph of the grandstand by Jennifer Colten.

His pride and joy was Jones Park. It was the most elaborate of his parks and he took great care to ensure that it was a source of pride for the community. Griffin bit off more than he could chew with the acquisition of Lake Park, however. Though it was maintained throughout his lifetime and he never gave up hope that it could be developed into a gem, the large park became burdensome for the park district and was eventually sold to the state.

Mr. Griffin was kindhearted and was involved in many charitable events and organizations, including the Knights of Columbus, for which he planned the annual banquet for many years. Griffin also sat on the St. Clair County Housing Authority board that managed the new concept of government-built and -managed housing for people who could not otherwise participate in the housing market. Griffin’s service was honored in 1953 with the dedication of the Emmett Griffin Homes. The housing complex still operates as the Villa Griffin homes at 2630 Lincoln Avenue in East St. Louis, on land that was once part of Lansdowne Park.

Aerial view of Jones Park, looking North, showing the massive water feature. SIUE Institute for Urban Research.

This park is across Caseyville Avenue from the Jackie Joyner-Kersee Center. The “JJK” Center is named for the Olympic gold medalist who hails from East St. Louis. As a way of giving back to her community, Joyner-Kersee established a foundation to build and operate a facility that provides fellowship for young people, allows them to develop athletic and personal skills, and gives them a safe place to be after school. Open since 2000, it has weathered early financial difficulty and is again operating fully. Joyner-Kersee remains active personally in the facility and its programs. It provides after-school programs for kids and serves as a Head Start center as well.

Adjacent to the JJK property and Lansdowne Park is the Emerson Park neighborhood. Emerson Park is remarkable for a few reasons. First, it was the site of major housing redevelopment in the city. Beginning in the 1990s, urban planners with the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign began to work with neighborhood leaders, local officials, and the developer McCormack-Baron to develop “Parsons Place” in three phases. This housing development has been successful by all measures. It remains an oasis of quality housing in a city that still struggles to find good housing for all of its residents. It also sparked neighboring developments with the redevelopment of the Central City homes and the addition of senior housing in the Jazz at Walter Circle development.

Second, there remains the Immaculate Conception Church at 1509 Baugh Avenue. This church is significant because it historically served the Lithuanian population of East St. Louis, and the descendants of that population keep it going today. It still retains its ethnic parishioners, though they no longer live in Emerson Park. Catholic Mass is still celebrated there on occasion.

Third, Emerson Park retains one of the old historic industries—paint pigment manufacturing. George Mepham opened his paint factory at North 20th Street and Lynch Avenue.26 The business changed hands many times, but remains active today as Rockwood Pigments. The plant manufactured, among other things, oxides used to color paints. Some argue that there are still streets in Emerson Park that glow red in the summer sun due to years of exposure. On a sunny day, go to the corner of North 19th Street and Lake Avenue and see for yourself.

-

Cairns, Malcolm. History of Illinois Park Districts: Decade by Decade. Posted: 1997. Accessed: January 6, 2016. http://www.lib.niu.edu/1997/ip970923.html. Web.

-

Elazar, Daniel. American Federalism: A View from the States. 2nd ed. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1972. Print. Pp. 94, 117.

-

National Recreation Association. Playgrounds: Their Administration and Operation. George D. Butler, ed. New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, Inc. 1936, 1.

-

Ibid., 1.

-

Charlotte Rumbold Papers 1846-1946, Missouri Historical Society. http://www.mohistory.org/files/collections/file_upload/Rumbold_Charlotte_Papers.pdf, posted 3/2008, accessed 4-22-16.

-

Nunes, Bill. East St. Louis, Illinois: A Year-by-Year Illustrated History. Dexter, MI: Thompson-Shore, 1998. Print P. 45.

-

Ibid., 68.

-

“Frank Holten State Recreation Area,” StateParks.com. http://www.stateparks.com/frank_holten_state_recreation_area.html. Posted: n.d. Accessed: January 24, 2016.

-

Nunes, 1998, 73.

-

Nunes, 1998, 75.

-

Nunes, 1998, 246.

-

Nunes, 1998, 246.

-

Nunes, 1998, 246.

-

Nunes, 1998, 246.

-

See Theising, Andrew. Made in USA: East St. Louis. St. Louis: Virginia Publishing. 2003. There are many books on the 1917 Race Riot.

-

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “North Alcoa Site, Operable Unit 1,” Region V Cleanup Sites. http://www3.epa.gov/region5/cleanup/northalcoa/ Posted October 2014. Accessed: January 24, 2016. Web.

-

See Fuller, R. Buckminster and Kiyoshi Kuromiya. Critical Path. New York: St. Martins Press. 1981. Print.

-

“Our Locations,” Lessie Bates Davis Neighborhood House. http://www.lessiebatesdavis.org/our-locations/ Posted: n.d. Accessed: January 24, 2016. Web.

-

Theising, 2003, 83.

-

Theising, 2003, 190.

-

Nunes, 1998, 49.

-

Nunes, 1998, 50.

-

Nunes, 1998, 212-213.

-

Nunes, 1998, 50.

-

See, for example, “Park Superintendents in Annual Meeting,” Park and Cemetery, Volume 27. Pg. 194.

-

Nunes, 1998, 40.