Company Towns

Jesse Vogler

What is the horizon of town-ness? Is it a social bond between people? Is it a territorial demarcation of incorporation? Is it a common set of values shared by citizens and government alike? The company towns of the American Bottom challenge many of the longstanding assumptions that we bring to our understanding of what constitutes community, as 19th and early 20th century town development in the East Side followed patterns that brought municipal incorporation and corporate incorporation ever closer.

This itinerary seeks to tell an urban, political, and social history of the American Bottom through the seven company towns that were chartered here in its industrial height as it theorizes a broader landscape of division. In the incorporation, dis-incorporation, and afterlife of company towns in the American Bottom, we can read narrative of civic and social responsibility that is often at odds with the industrial imperatives of the time. If there was a shared attitude toward extraction, production, and capitol accumulation, then the sharp discontinuities and spatial fragmentation speak to the limitations of industrial production to address civic and social concerns. This itinerary will attempts to develop a synthetic language—both visually and written—through which we can begin to interpret this episodic landscape.

Roxana, IL. Photo by Jennifer Colten

Marking one of the densest clustering of company towns in the country, the portion of the American Bottom lying directly East of St. Louis is home to seven distinct pairings of industry and municipality. Chronologically, these pairings are as follows: Granite City/National Enameling and Stamping Company (NESCO); National City/ St. Louis National Stockyards Corporation; Hartford/ International Shoe; Wood River/ Standard Oil; Roxana/ Shell Oil; Monsanto Town (now Sauget)/ Monsanto; Alorton/ Aluminum Corporation of American (ALCOA). Across these pairings emerge patterns of industrial land ownership, concerted real estate practices involving land disposal or lease, and the provisioning for employee housing. While this is already a dense collection for such a small geography, if we were to simplify the definition of company town to those incorporated entities whose economic and social existence is dominated by a single industry, the list could be expanded to include East Alton/Olin Brass, Madison/Commonwealth Steel, Fairmont City/American Zinc, and perhaps Dupo/Missouri Pacific.

While this itinerary focuses on these company towns in the period of industrial expansion, it bears noting that in the long history of the Illinois Country we can find a singular episode of corporate land speculation that inaugurated the company town in the region and which brought about what many consider to be the first speculative land bubble in the globalization of capital. In 1717, Scottish financier John Law and the regent of France, the duc d’Orleans, founded the Company of the West, later the Royal Indies Company, with the explicit intention of developing the economic resources of the upper Mississippi River valley. In an episode of economic and political hubris, Law enthusiastically sold shares in this interest, known more popularly as the Mississippi Company, back on the Continent with promises of nearly unbounded capitalization to be gained from exploiting the natural resources of the region. When this did not occur, public confidence in the Company and Law plummeted and the unfulfilled debts and obligations combined to burst what was then the first land bubble—known to historians as the great Mississippi Bubble. Undeterred, the reorganized company sent an emissary of three persons to serve as a Provincial Council, with a speculative miner, Philip Renault, to manage extractive operations in the field. This provisional council found Fort de Chartres to signal French military and governmental presence in the far-flung interior, and also to serve as an entrepot for the Company’s mining transactions. Renault, for his efforts, was granted one of the largest concessions on the Bottom, on which he founded the town of St. Phillipe as an agricultural provisioning community for his mining operations elsewhere. Here, he settled a few dozen farmers and slaves in a territorial diagram that explicitly linked hinterland extraction with an agricultural base built around a company town. In these two enclaves, we might then locate a nascent company town typology that can be seen as a defining settlement type of the American Bottom that continued up into the 20th century.

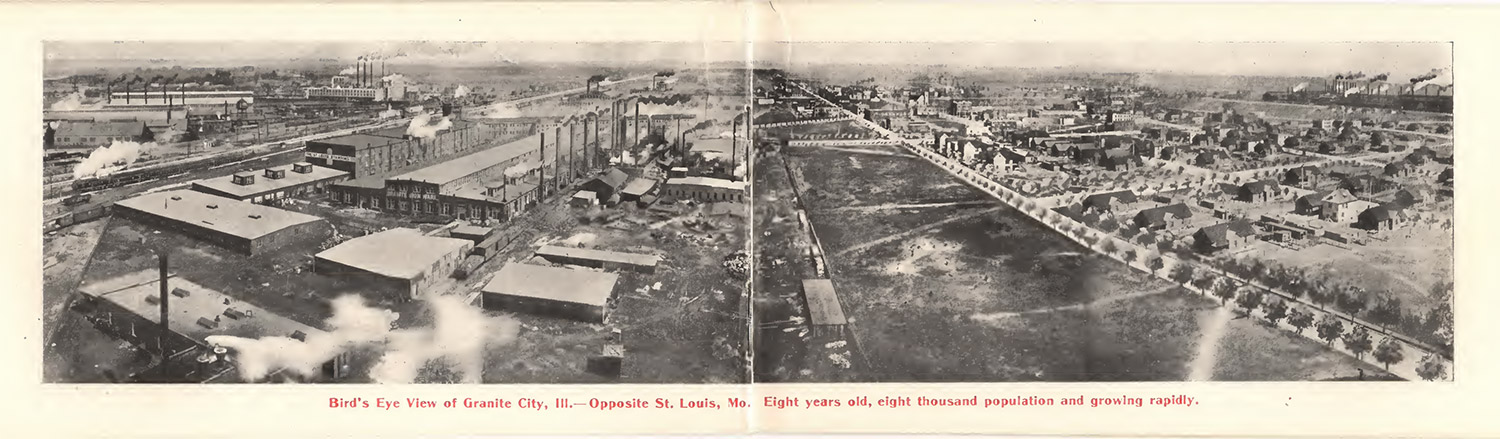

If we can read in the garrison of Chartres and the agricultural lots of St. Phillipe a symptom of colonial empire on the eve of large-scale European settlement, then in the slaughterhouses of National City and the industrial planning of Granite City we can read the surplus or externalization of the growth of St. Louis in its years of industrial development. “The East Side has rapidly become,” writes Graham Taylor in his seminal 1915 study on Satellite Cities, “the section of the St. Louis industrial district into which heavy industrial processes, usually the dirtiest and dingiest, have been shunted.” This landscape of industrial suburbs is marked by extreme spatial fragmentation—with each town structured around its own industrial core and in many ways closed off and even antagonistic with its neighbors. Rail lines and infrastructure recapitulate the invisible boundaries of municipal incorporation, objectifying and rendering durable these already strong urban divides. The social consequences of this are equally stark, with Taylor writing that the “special dividing lines across which industry jumped to secure unusual economic gains have meant unusual civic isolation.” Within these enclosed industrial fiefdoms, it was simply left to the prerogatives of industry as to the social horizon of their associated towns—and it may be one of the defining characteristics of company towns that civic aspirations tended to be hemmed in by the immediate industrial interests of the parent company.

And this is perhaps where this study is most instructive: in a new understanding of company towns not only through a set of case studies, but as a defining condition of the territory.

Lying at the heart of this division are the latent territorial rules of the region. By rules, I mean to highlight the creative, if ignoble, convergence of natural and administrative constraints that give rise to specific social and spatial patterns. Which is to say, rules that produce certain territorial effects while restricting others. Here, I would like to foreground three of the defining constraints and conditions that have, I argue, overdetermined the spatial and social history of the American Bottom during the crucial years of industrial expansion. I frame each of these constraints as a particular coupling of so-called natural determinants and a related set of administrative/cultural practices. While individually these constraints have long been identified in the growth of East Side industry, the mutually affirming relation between them has not been properly clarified or framed.

First, the abundant presence of cheap coal in the Illinois coalfields coupled with lax nuisance laws produced a receptive environment to the defining smokestack industries of the time. Coal gave rise to the both the nature of specific industries as well as the means of transportation to bring it to market—with the very first railroad in the region constructed from the coalfields near Bellville across the floodplain to the riverside ports of Illinoistown. But it was only by defining an administrative garrison from the more strict nuisance and smoke laws of St. Louis that this resource was able to achieve the scale it did. In a era prior to comprehensive zoning, nuisance laws were a crude way for municipalities and civic leaders to steer development and incentivize (or de-incentivize) the location of factories. Many of the East side industries incorporated as their own towns in order to be able to steer this particular instrument in a manner more forgiving to industry.

Second, the availability of large parcels of relatively cheap bottomland coupled with the large-scale drainage and flood prevention infrastructures that thoroughly transformed the ecology of the floodplain. By reframing the floodplain as a speculative real-estate opportunity, the American Bottom was naturalized as a site for the large-scale industrial footprints that have come to define the land use of the region. Once this speculative framework had taken hold, it was a short step to argue for the massive investment in levee and drainage districts that further facilitated and capitalized the already productive landholdings of industrialist. While early-on this infrastructure was industry or municipality specific, in the early years of the 20th century an inter-city, regional group was incorporated to effect this management on a comprehensive, regional scale. So while early towns and industries tended to locate on high-ground above the historic floodline, the East Side Levee and Sanitation District effectively rendered the entire American Bottom of the Metro East as an accessible extractive and productive landscape for industry and real-estate.1927—5-35 cents in TriCities and 5$ in Mill Creek Valley

Third is a sort of triple coupling that relies on the twin boundaries of the Mississippi River as a physical boundary and the state line as an administrative boundary, coupled with a financial instrument uniquely manufactured to capitalize on both these divisions: the aptly named Bridge Arbitrary. This Arbitrary was an overarching tariff on all good crossing the Mississippi River and State Line on the Terminal Railroad Association bridges—with, for example, a nearly 20 cent ‘flat tax’ added to every ton of coal that crossed this divide, regardless of distance traveled. We might be more prone to believe the contemporaneous arguments by the TRRA as to the infrastructural imperatives of the Arbitrary if its board was not made up of East Side industrialists and landholders whose manufacturing interests and real-estate were to receive the greatest benefit from this tax.

In what follows, this itinerary will chart a narrative through the regulatory framework of municipal incorporation, the architectural coupling of industry and worker housing, and the social aspirations (or lack thereof) of the communities that lived in these satellite cities. Through 6 case studies XXXX With perhaps the exception of Granite City and NESCO, none of these Company Towns provided a compelling or strategic vision relating town planning with broader social and labor conditions. Rather, these are towns whose planning and architecture recapitulated the economic imperatives of their founding—which is to say, the towns all shunned any picturesque planning for a simple gridiron street pattern, and houses were generally simple utilitarian homes and duplexes to house employees. In the mail order homes of Wood River and the bungalows of Sauget, then, we can read the industrial imperatives of this region running counter to any civic aspirations their inhabitants might have had.

Wood River | Standard Oil

Looking North over the former Standard Oil refinery. Photo Jesse Vogler

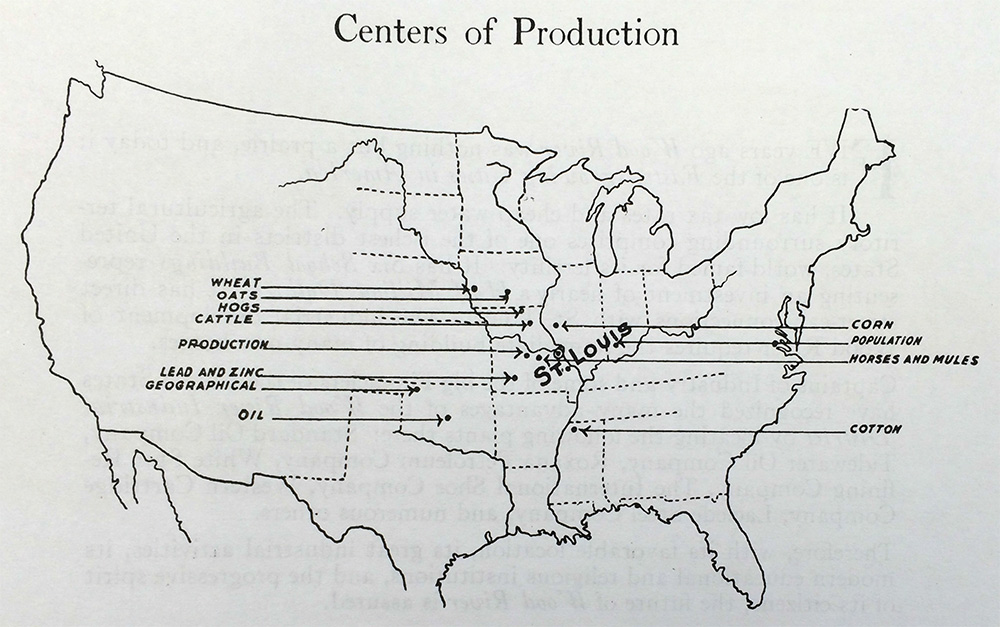

There is, in the ubiquitous booster literature of the second decade of the 20th century, a nearly teleological bent to the Wood River success narrative. To an eager real-estate market, Wood River’s inevitability is argued in terms both industrial and demographic. “Centers of production have closed in and around Wood River until within a radius of one hundred and seventy-five miles are the centers of production of Coal, Wheat, Oats and Cattle,” outlines one real estate catalog, while “the Center of population of the United States has moved steadily westward in a line practically straight toward Wood River since 1790.”

This simultaneous pairing of a rhetoric centrality and periphery is itself a technique common to speculative . As if to make up for the inevitable gap between sites of extraction and sites of production, real estate interests argued that an ambiguously defined “point of economic assemblage is the important decision to reach,” an assemblage that incorporated the interrelated considerations of production, extraction, transport, and labor.

Gotman Real Estate Catalog, 1912.

Early photographs and descriptions of Wood River show a settlement more akin to the mining-camps of the west than the municipal aspirations of most Midwestern towns. With tents, clapboard buildings, and muddy tracks as streets, Wood River began as little more than an unchoreographed clustering of industry and workers. From this early settlement the community of Benbow City emerged. Mostly catering to the more profane aspects of labor concentration, this ‘City’ was primarily a clustering of taverns, brothels, and gaming houses that catered to the rapid influx of workers to the area. While Benbow City cannot be counted as a direct instrument of Standard Oil, it was nonetheless a symptom of the rapid growth in the area and stood in material contrast to the more orderly city of Wood River that was growing up adjacent. In a telling anecdote, speaking to both the social and regulatory divisions between these two communities, a duel was fought between two policemen of the rival towns, each standing in their respective towns straddling the boundary, in which the officer from Benbow was killed. Later, following a large flood in 1915 that all but destroyed Benbow City, Standard Oil bought the site of Benbow, tore down all remaining buildings, and fenced off the area.

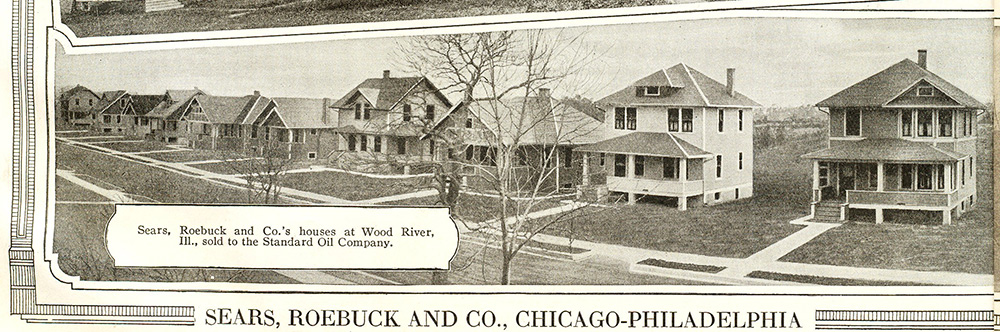

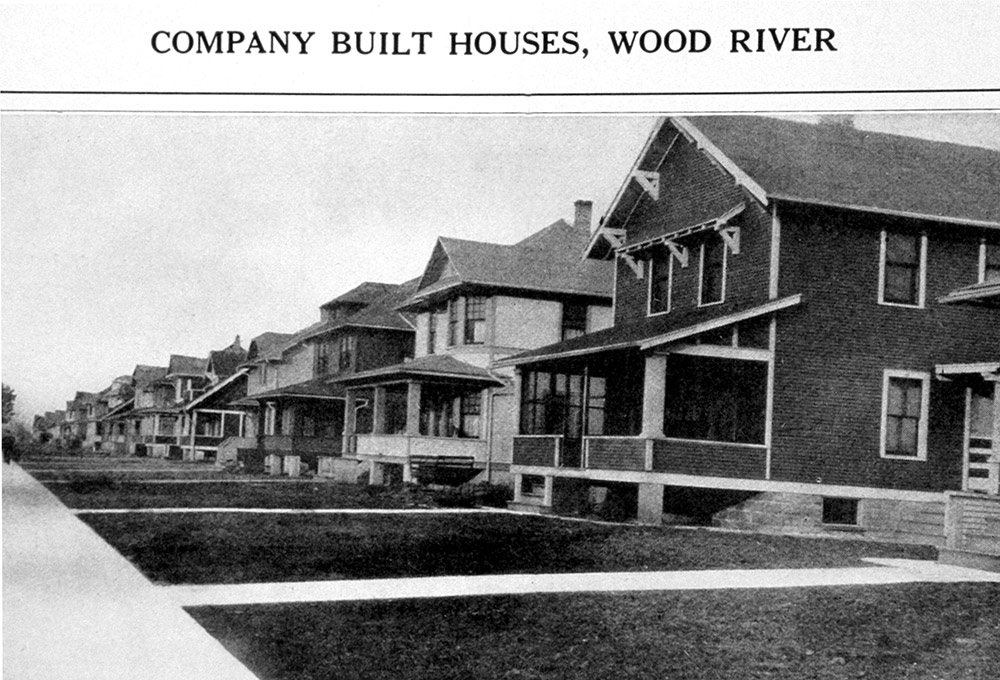

Into this volatile civic environment Standard Oil took the step of ordering the construction of dozens of houses for workers and administrators of the Refinery. In an episode that is one of the more compelling local architectural histories, in 1918, Standard Oil ordered the construction of nearly 200 Sear’s Mail Order Homes across three sites in Southwestern Illinois. Sear’s Roebuck & Company had been organizing the logistics of their Honor-Bilt Homes for nearly half a century. Homes would arrive flat-packed on railcars, with every piece of the house—from pre-cut framing to nails to wainscoting—tabulated and accounted for in the instructions to builders. Site-work and foundations were to be done on-site per the specifications provided in the specific model home, while relatively unskilled carpenters could achieve the erection of the houses.

Sears Mail Order Homes, 1920. Courtesy Rosemary Thornton.

The mail-order home phenomenon can be seen as less of a specific building technology and more as a comprehensive territorial or cultural technology that company towns are also a part. By cultural technology, I intend to highlight the . In this view, the specific technology of the Mail Order homes incorporates the hardware of railways, building materials, and related infrastructures, as well as the software of the Post Office Department, the printing infrastructure of the Catalogues, and the protocols of the instruction manuals.

Additionally, worker housing was seen to play a pedagogical and normative role in the broader social history of the city, with one real estate catalogue claiming: “The foreigner, however, in Wood River, is so overwhelmingly surrounded by the long-Americanized type, that he all the more quickly absorbs our methods and ideas, and the sooner grow in proficiency and value. This is probably due to the fact that a large percentage of the workmen occupy their own residences.” As such, to the range of instruments that make up the territorial technology of greater Wood River we must also add the specificities of the labor situation; a situation that emphasized assimilation, on the one hand, and the ‘great elasticity’ of an hinterland agricultural workforce one the other.

Sears Mail Order Homes, 1920. Courtesy Rosemary Thornton.

Mail order homes were only a piece of the infrastructural town-building activities of the parent industry. In a letter from Standard Oil to the contractors tasked with erecting the homes, a company representative writes:

The two hundred (200) houses which you built for us a Carlinville, Wood River and Schoper, Illinois are now completed and are entirely satisfactory in every detail. The workmanship, laying out of streets, sidewalks, sewers, etc., has all been handled in a very satisfactory manner, and the quality of the material is exceptionally good. We are proud of the architectural appearance also the convenient arrangement of rooms in these houses, and we are able to offer these houses to our workmen at very low prices.”

We can see here the comprehensive nature of this sort of city building, with the entire suite of urban infrastructure—from streets to sewers to sidewalks to housing—carried out by a single entity at the behest of a central industrial and landed interest. City, housing, and industry were organized, planned, and carried out by a central agency.

Alongside this infrastructure of inhabitation, Standard Oil also invested in numerous civic amenities throughout the city—with schools, municipal clubs, and parks all bankrolled by Standard. Of particular interest, and point of local pride for many decades, was the city park built on the North side of town. Opened July 4, 1926, this park was soon to be home to the Country’s largest swimming pool. At 300’x200’, and 1.32 million gallons, the pool was the largest in the country and was built by Standard Oil for some $100,000. Opening day initiated what would become the annual Mermaid Beauty Contest.

Roxana | Shell Oil

Roxana, Il. Photo Jennifer Colten

Known for its ramshackle appearance in the years following its founding, Roxana would carry the name of ‘Mudville’ through the first decade of its existence. While noting that the town had outgrown its ‘jerry-built aspect’, the writers of the 1939 WPA Illinois Guide still made note of the “acrid odor of oil that pervades the town on summer days;” an odor “frequently noticed by visitors, but imperceptible to residents.” An outgrowth of the Royal Dutch Shell enterprise, a refinery was sited here in 1917 and named Roxana was named after the Shell subsidiary, Roxana Petroleum, that would run the refinery.

Like its predecessor, Standard Oil, to the north, Shell owned the land on which the associated refinery town was to be developed, and they set out on a coupled path of industrial and residential development. As part of its recruitment package of luring workers to this relatively unpopulated area, Shell had built a series of company houses that were offered at cheap prices near the plant along Tydeman St. The so-called Hancock Houses, named after the Raymond O. Hancock & Co, a Chicago based operation contracted to build the homes. Additionally, staff houses were built on refinery property for managers that were on-call at all hours of the day and night.

More unforgettable is the piercing moan, as of some great beast in pain, that often comes at night when the stills are shut down for cleaning—the sound of whirling brushes sweeping through the vast network of pipes.

In the early years of the refinery, a large goat herd was kept to manage weeds and grass around the refinery buildings. However, by 1929, the goats had become an operational hazard—occupying the railroad and switching yard, causing delays in delivery.

Hartford | International Shoe

In keeping with a pattern of preliminary production that is a signal characteristic of American Bottom industry, in 1916 International Shoe built what was then one of the largest leather tannery facilities in the country. Sited near an abundant water source and sited just north of what was then the second largest stockyards in the country, the factory procured their hides from National City Stockyards and their water used in the tanning process from the Mississippi River. Within a few years, in a town of 1,600 people, 900 were employed at the tannery. Recognizing the singular role the factory played in the development of the village from a loose clustering of agricultural homesteads to a town proper, in 1920, on the eve of incorporation, the town considered naming itself "Tannersville."

The Hartford facility prepared hides for manufacture into finished products elsewhere—primarily in a distributed set of factories located in rural Illinois and Missouri towns. In this we can read a fascinating territorial diagram that links centralized and decentralized production within a continuous operation. Taking advantage of the changing labor dynamics due to mechanization in rural America, International Shoe’s rural factories in some ways point to an earlier era of piecework that was the hallmark of the rural domestic economy.

International Shoe built a small number of company houses, but more tellingly the Company built a motel cum boarding house on the grounds where workers could stay during the week—only to return to their rural, agricultural homes to work their land during the weekends. In this architectural type we can read a more widespread anxiety around rural/urban relations that marked this decade. It was in the 1920 Census report that the urban to rural ratio—that supposedly grand arbiter of planetary urbanization—was to announce that more people now lived in cities than in the country. Of course, these designations are cut to the heart of the very definition of the American Bottom—as this interval complicates any easy categories we might bring to the urban/rural distinction. For in the complex of levees, ditches, railroads, industrial expansion, and perhaps even in the modest boarding house of International Shoe, we can read the longstanding prediction of Marx to the urbanization of the countryside.

Looking NE over Hartford from Confluence Tower. Photo Jesse Vogler

The material processes of operating the tannery are important here to understand the relationship between American Bottom industry and an evolving conception of nuisance law. Tanning was a 37 day process that included 8 different washes, including initial washings and soaking, a chemical treatment for dehairing, a lime wash, salt and sulphuric acid treatments, a chromium sulphate and salt wash for tanning, and a final dying process. Significantly, well over 1,000,000 gallons of water were used every day, with over 9,500 pounds of suspended solid being discharged into the Mississippi daily. Following a 1936 study by the Illinois Department of Health that noted the negative effect this effluvia had on downstream water supply, in 1938 International shoe constructed a large settling basin, 1200’x275’x5’, to remove some of the solids from the water before passing the water into the Mississippi. In a telling detail, however, this settling basin is not constructed within the levee protected area—lying instead on the floodable side of the levee line. And while International Shoe closed its Harford plant in 1964, this basin remains as an embedded landscape record.

Yet the noxious odors of the tannery were not the last nuisance left for Harford residents to address. For the past 50 years, Hartford has been the site of expanded EPA studies and legal action related to gasoline and benzene leaks that have left, by certain measures, a plume of over 4 million gallons of hydrocarbons floating atop the local groundwater—with this oval-shaped hydrocarbon ‘pool’ measuring from 5 to in excess of 24 feet in thickness. As the level of the water table is subject to variation based on the river stage and local rainfall, sometimes this plume rises to the level of Harford basements and a distinct gasoline odor is present throughout the community. Beginning in 1970, ignition of this plume has led to a number of fires and house explosions in Harford—though Fire Department reports often attribute the cause of the fire to the ignition of ‘sewer gas.’

In one of the more candid assessments of potential risks posed by industry located in floodplains, much of the 2008 case where Apex Oil was found liable rested on a detailed description of floodplain dynamics and soil strata. Here, they describe geologic conditions that promoted the accumulation and migration of leaked hydrocarbons beneath the Village of Harford through a porous layer known as Main Sand. But more importantly, they point to the inherent continuities within the geological footprint that make the isolation of risk, hazard, and fallout nearly impossible.

Granite City | National Enameling and Stamping Company

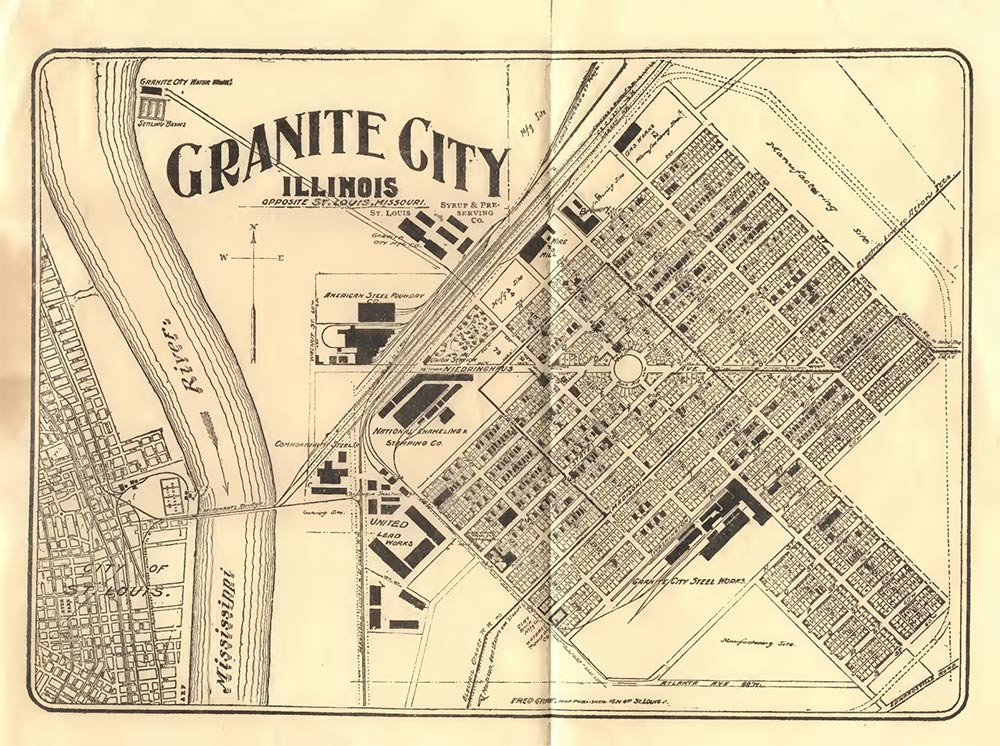

Overview of Granite City in 1903. Granite City Real Estate Booklet

GRANITE CITY STOP COMING SOON

Granite City town plan. Granite City Real Estate Booklet

National City | National Stockyards

House slabs, National City, IL. Photo Jesse Vogler

As Highway 3 makes its way under the new bridge, we enter a vast, empty tract of floor slabs and partial ruins. This is the site of the former National City. Once a company town and home to the largest hog market in the world, National Stockyards underwent a period of intensive industrial capitalization in the last quarter of the 19th century, and a parallel disinvestment in the later half of the 20th in a pattern recognizable across much of the region’s industry. During its zenith in the early 20th century, 50,000 animals were processed weekly—nearly eclipsing the storied Union Stockyards on the south side of Chicago. Today, little remains as a reminder of this immense industry. In 1996, the city evicted all of its residents, officially disincorporated as a municipality in Illinois, and soon thereafter nearly entirely razed its facilities--thus affecting an erasure of a specific historical moment in the history of the American Bottom development.

At a Council meeting on July 17, 1872, ‘covenants of mutual advantage’ were given and received by the city of East St. Louis and the St. Louis National Stockyards Company. At the time, East St. Louis was itself in the throes of a municipal identity crisis—with dual mayoralities claiming control over the city’s affairs. Into this civic uncertainty, the National Stockyards Company agreed to construct a “magnificent” hotel of stone, costing not less than 100,000 dollars, and to construct a Stock Yards “to exceed in importance, magnitude, and completeness” any like institution of the kind in the country. For their part, East St. Louis covenanted to abstain from infringing upon the land owned by the Company, agreeing to not construct any improvements on land owned by the Company and to never enter into annexation procedures.

The scale of the operations were staggering, with an entire range of infrastructures—from financial institutions to sewers—giving shape to what many called a city unto itself. At its founding in 1873, National City was the only municipality in the area with paved roads, electricity, and fire hydrants—with many commenting that the soon-to-be-slaughtered animals had better water than people living in next door East St. Louis. It housed one of the most opulent hotels in the area (the Allerton House) and, perhaps unsurprisingly, one of the more sought after steak-house restaurants—known for serving 300 dozen eggs during its Monday morning breakfasts. Of the 656 acres that the Company owned, 100 acres were under shelter with much of the rest enclosed in yards built of cedar posts and paved with locally produced bricks. Waterworks were constructed in 1873 on neighboring Cahokia Creek—with a capacity of 600,000 gallons connected to the city’s 27 fire hydrants. Additionally, members of the Company board incorporated the East St. Louis and Carondelet Railway—better known as the Conlogue line—connecting the stockyards with the Ferry terminal at East Corondelet. Explicitly built as a transfer line, the Conlogue brought stock from virtually all points west of the Mississippi across the river in bulk-ferries and then up the riverfront to the Yards—in a crossing that bypassed the TRRA monopoly on crossings in the downtown area.

As an economic instrument, the Stock Yards looked to make up in volume the narrow margins of this type of industry. In the vast scale of land-holdings owned by the Company we can read an early intention for the co-location of associated industry. In a sort of industrial piggy-backing that is common across many industrial sectors, horizontal diversification gave rise to a number of integrated industries—with tanneries, slaughterhouses, packing houses, rendering plants, and grinding mills all quickly locating on Company land adjacent to the stockyards. Armour, Swift, Royal, and Hunter were all national interests opening packing plants in the area, in a cycle of east-coast investment Andrew Theising calls the 'nationalization of local interests".

In 1907, fearing possible annexation would in fact be carried out under new city leadership, owners of the Stock Yards began the process of municipal incorporation in a sort of legal defensive measure. As owners of all the land of what would become National City, National Stockyards Company built just enough company-owned, worker housing to officially incorporate as a municipality—a statute requiring a minimum of 50 residents in Illinois. By incorporating as its own municipality, National City and its industrial interests insulated itself from the uneven and sometimes volatile administrative and regulatory environment of East St. Louis to the south.

With regional pressures voicing opposition to a slaughterhouse so close to the city of St. Louis, and the decentralization of hog processing in the middle 20th century with the rise of the Interstate Highway System and the concomitant growth of trucking over rail, National City slowly wound down its operations. Residents were ordered out by April 1996 following a vote by the Village Trustees a day earlier authorizing the construction of a $2 million topless club. Villagers were evicted on August 2nd, and the houses subsequently torn down. After the Board of St. Claire County called for a special census, the US Census found that the city had zero residents. Citing a statute somewhat unique to Illinois, the Board was able to call for the dissolution of an incorporated place if the population falls below the 50 person threshold in the most recent census. After a short appeal, the dissolution was affirmed in October 1997, with National City’s incorporated status coming to an end.

While Armour packinghouse was the first plant to close in the postwar years (1959, 1400 employees), it was the last to remain standing. The two smokestacks of the main building were the only remains of this vast slaughterhouse until, in 2016, these too were destroyed in the final erasure of National City. Today, if you visit Vail, CO, you can find a city built for tourist paved with the old National City bricks. A final material and spiritual dislocation of this once thriving productive landscape.

I-70 signs waiting placement on new route. National City, IL. Photo Jesse Vogler

Alorton | Aluminum Corporation of America (ALCOA)

North ALCOA Site. Photograph by Jennifer Colten

Tucked along the end of the industrial corridor of East St. Louis, between Bond and Missouri Avenues, are the remains of the Aluminum Ore Company factory and its associated town—Alorton. Between 1902 and 1939 the factory held a monopoly on the North American continent for the preliminary refining of bauxite ore into alumina, and during this period this East St. Louis plant (once the largest employer in the city) produced every ounce of aluminum in the country. While there is little to distinguish the existing town from surrounding communities, it remains a distinct municipality within an already fractured municipal landscape. Like many of the industrial towns in the region, Alorton was incorporated as a distinct municipality in order to more completely control nuisance laws and to distinguish it from the already troubled associations with East St. Louis. Yet despite these origins, in 2014 a prominent business magazine dubbed Alorton “The Most Corrupt Village in America,” with both the mayor and police chief serving jail time for a variety of misconduct.

To the northeast of Missouri Avenue, across from the Metro East and Fluoride Industrial park, are the vast settling ponds of the former factory. The site, now bearing a two-foot earthen cap, was remediated with a novel brownfield strategy: the town partnered with Brightfields Development to use site remediation as site prep-work for a 20-megawatt (MW) solar farm development. It carries the promise to hold a 100-acre solar panel farm—the largest in the Midwest—hinging on a bill in the Illinois state legislature that would require local utilities supplier Ameren to purchase electricity from the site for the next 20 years.

To the south of town are the community of Centreville and the huge hump yards of the Alton & Southern Railway Co.—organized to add engine capacity to overcome the relatively steep slope of the MacArthur Bridge approach. Originating in this yard is the “Black Bridge”—so named both because of the hulking black trusses of its overhead viaduct and its de-facto boundary to black migration from the South—which feeds the slender MacArthur railway bridge across the Mississippi River into downtown St. Louis.

Sauget | Monsanto

Painting in City Hall multipurpose room. Sauget, IL. Photo Jesse Vogler

Few towns in the American Bottom epitomize the industrial imperatives of the region as thoroughly as the town of Sauget. Originally incorporated in 1926 as Monsanto Town, the town was founded explicitly as a “community of chemical-using industries” in an effort to establish a nearly regulation-free zone for industry and business. Following the principles of the “Irwin System”, the founders believed that a company would receive favorable publicity by having cities containing plant sites bear the company name. While many communities on the eastern side of the Mississippi welcomed the so-called ‘smokestack’ industries that civic-minded St Louis leaders would not tolerate, Monsanto took this to an extreme—finding even the regulations and restrictions in neighboring East St Louis to be too restrictive. As its name suggests, the Monsanto company had their primary chemical plants in the city, but with the production and use of PCBs, and its ties to this company, the city leaders decided to change the name to the less attention-grabbing name of Sauget—named after the first village President. While the town would today basically just be called an industrial park, the town nonetheless has the ignoble legacy as being the only North American PCB manufactory until 1977, and remains one of the most polluted areas in the entire country.

Today, if you stand at the intersection of Route 3 and Monsanto Ave, you can see the extent of this town: Big River Zinc (NE corner: at one time the third largest zinc smelter in the country), Center Ethanol Plant (SW corner); former Monsanto plant (SE corner); Cerro Flow Products (manufacturer of blue urinal discs); the American Bottom Wastewater Treatment Plant (servicing nearly the entire Metro-East region); the Sauget Chemical Treatment Plant (one of only three such municipal plants in the country); and further west the six stacks of the Cahokia coal fired power plant and the 3 or so adult entertainment clubs that have given the area the nickname of ‘Sauget ballet’. Around the bend are a number of points of interest, including: the St Louis Building Arts Foundation—a material archive of architectural and industrial objects from cornices to entire iron storefronts to stained glass; the Cahokia ‘superpower’ plant—which was the largest power station at the time of its completion and whose 265 foot stacks are a familiar site from the opposite side of the river. Further out is the Downtown St. Louis Airport (a great spot for chartered flights around the city) and a new ballpark for the minor league Gateway Grizzlies.

Metro-East Police Dog Training Park. Sauget, IL. Photo Jesse Vogler

-

Andrew Theising. Made in the USA: East St. Louis. Virginia Publishing, 2013.

-

Graham Romeyn Taylor. Satellite Cities: A Study of Industrial Suburbs. New York: D. Appleton And Company, 1915.

-

Margaret Crawford. Building the Workingman's Paradise: The Design of American Company Towns. New York: Verso, 1996.

-

Hardy Green. The Company Town: The Industrial Edens and Satanic Mills that Shaped the American Economy. 1883.

-

Robert Koepke. “Manufacturing in Metro East.” Bulletin of the Illinois Geographical Society, 16:1, 1974.

-

Doris Rose Henle Beuttenmuller. "The Granite City Steel Company: History of an American Enterprise"

-

Stanley Buder. Pullman: An Experiment in Industrial Order and Community Planning 1880-1930. New York: Oxford UP, 1970.